"... the most complex ecosystem on Earth ... the tropical rain forest is one thousand times more biologically complex than the tropical reef system, the second most complex system on Earth, with one million times greater biodiversity than our own ecosystem here."- Mike Robinson, Director of the U.S. National Zoo

In this lesson, we will learn:

|

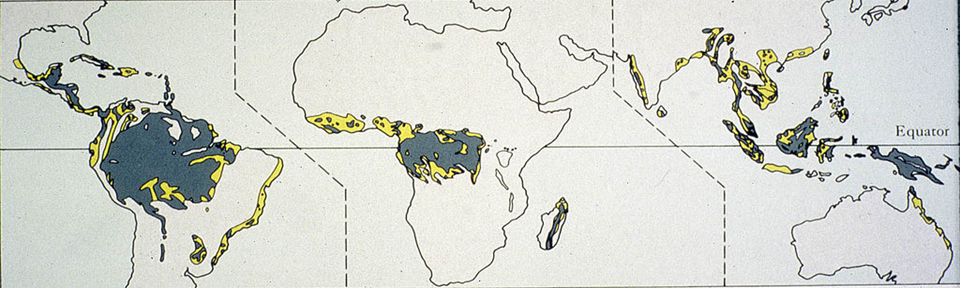

IntroductionIn previous lectures we focused on general principles of ecosystems, emphasizing the processes of biogeochemical cycling and energy transfers. In this lecture we will look at one ecosystem in detail, the tropical rain forest. There are several reasons for this. First, ecosystems may all function according to the same basic principles, but they most certainly don't all look the same and it is important to have some understanding and appreciation of this diversity. Second, it is important to learn about the "specifics" of ecosystems as well as the "generalities". Finally, we can use this examination of the tropical forest to help tie together some of the material that has been presented in the ecology and evolution sections of the course. Today we will examine the most productive and diverse ecosystem found on land: the tropical rain forest. These ecosystems are also, and perhaps more accurately, called humid tropical forests. These ecosystems are also changing rapidly, as Figure 1 illustrates in terms of the past and present distribution of tropical forests on Earth. Tropical forests once covered 15-20% of Earth’s land surface (200 years ago, certainly post last-glacial maximum), and now they cover only about 5-10% of the land surface. Figure 1: Present (dark) and original (yellow) extent of humid tropical forest on Earth. Climate and GeographyCertain ranges of temperature and rainfall characterize the places where tropical rainforests occur, depicted in the following figures. | ||

Figure 2: Vegetation and latitude in Africa | ||

Temperatures generally fall between 23 - 27 deg C, with a greater daily than monthly range. In other words, there is no strong seasonality of temperature (unlike what we experience in Michigan).Rainfall tends to be highest near the equator, where the sun's evaporative power causes high evapotranspiration, and rising air cools and then sheds its moisture. Precipitation tapers off as one moves away from the equator, and dry belts are found at 25-30 deg of latitude (the great deserts). Local variation can also be great due to trade winds, ocean currents, land masses, and mountain ranges. Evergreen forests are replaced by deciduous forests as precipitation becomes seasonal. Wherever dry periods are several months or longer in duration, leaves are shed as the dry season takes hold, providing a winter-like visual appearance. Leaves re-appear in anticipation of or with the onset of the rains. (A dry month is one where evapotranspiration exceeds precipitation.) The growing season is thus shortened, and so forest productivity is less than in the evergreen forests of the more humid tropics. At lower annual rainfall (~1500 mm), forest gives way to savanna as can be seen in the vegetation map of Africa in Figure 2. Boundaries between ecosystems or biomes are often gradual, and they can be sensitive to changing conditions. A prolonged period of wetness or drought, or human intervention, can cause dramatic changes because of the transitional nature of environmental conditions near the boundaries between biomes. Humid tropical forests appear superficially similar everywhere, but in fact they differ widely in species composition and ecosystem attributes. In the coterminous United States, botanists recognize 135 natural plant formations based on dominant species, and driven by latitude and climate. This system is called the Holdridge system (Figure 3) and it is widely used for conservation purposes. However, its use is far from feasible in tropics. Instead, the future in classifying tropical rainforest plant formations may lie in remote sensing, where large areas can be mapped relatively quickly.  Figure 3: Holdridge vegetation classification system Nutrient Cycling and the Productivity of Humid Tropical Forests | ||

Figure 4: Tropical tree with thin topsoil and deep, unweathered rocks | ||

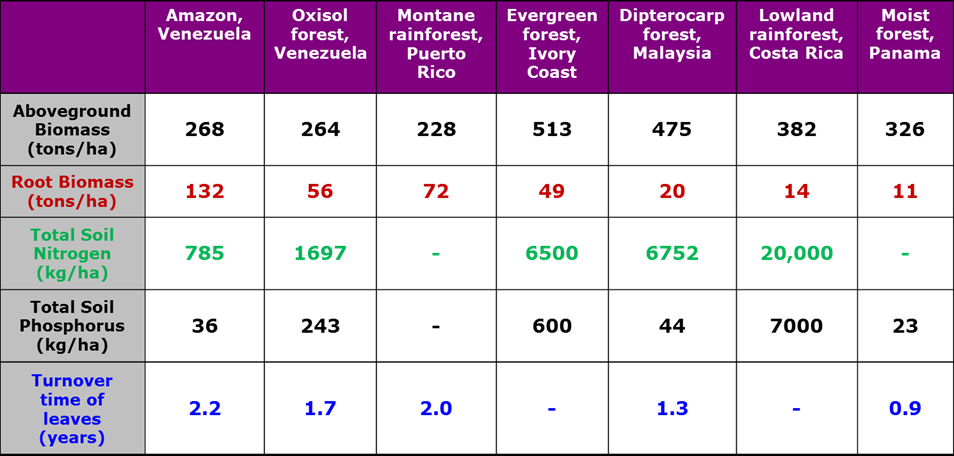

| The first Europeans to view humid tropical forests were stunned by the luxuriant growth, giant trees with huge buttresses, thick vines, plants growing on plants (epiphytes), and so forth. Such luxurious growth signals high productivity, and modern scientific measurements confirm this. If one measures the photosynthesis, or captures the litterfall of leaves, branches, fruit and other plant parts to the forest floor, one finds the production of tropical evergreen forests to be roughly double that of temperate forests. It would be natural to infer that tropical soils are very fertile in order to support this high productivity. But, as we have seen in other instances, or general inferences about what makes sense are often incorrect -- we must look more closely at the system and analyze how it functions. In fact, tropical soils tend to be very thin and the rock below them is highly weathered with few nutrients remaining (Figure 4). You already know that ecosystems are open with respect to nutrient cycling, meaning that inputs and outputs are significant. (Remember that the entire globe is closed with respect to nutrient cycling, because the inputs and outputs to Earth as a whole are extremely small.) What makes humid tropical forests so productive is the combination of high temperatures, light, and rainfall year-round (good growing conditions), coupled with especially efficient nutrient recycling. What is the evidence for this claim?First, analysis of soils of tropical regions shows them to be virtually devoid of soluble, mineral forms of nutrients. Rocks weather rapidly due to high temperatures and abundant moisture, and millennia of rapid weathering and torrential rains to wash away nutrients from the soils have left the soils very low in nutrient stocks. This is supported by the analysis of stream water draining tropical regions, which likewise reveals a scarcity of dissolved nutrients. Most tropical soils are clays with little soluble mineral content, and moderate to strong acidity which interferes with the ability of roots to take up nutrients. Only about 20% of the humid tropics has soils that can support agriculture, and most of this area is already in use.If the nutrients aren't in the soils, where do they come from? Figure 5 shows a budget accounting that indicates nutrients are found mainly in living plant biomass and in the layer of decomposing litter; there is little nutrient content of the deeper soil, as there is in temperate-zone ecosystems. This suggests that plants are intercepting and taking up nutrients the moment they are released by decomposition. There are many organisms that are players in this decomposition process: termites, bacteria, fungi, various invertebrates. Of particular importance are micorrhizal fungi that invade the roots of trees to obtain nourishment. As we learned in the lecture on Microbes, these fungi gain carbon nourishment from the tree and they benefit the tree by providing a vastly expanded nutrient gathering network in the soils. In some circumstances tree roots even grow upward toward the soil surface, permeating the litter layer. Isotope experiments have shown the importance of roots in nutrient uptake. For example, one study in the Amazon rain forest, which used Ca-45 and P-35, found that more than 99% of the nutrients added to the system (in the form of isotopes) were retained in root mats. More commonly, about 60 - 80% of nutrients are retained by the roots, and thus made available to the tree. The remaining 20 - 40% needed by the tree must be made up by fresh inputs, either from rainfall or rock weathering. What happens when the forest is harvested for timber or other plant products, or the forest is burned? In all these cases nutrients will be lost from the ecosystem, but the outputs cannot exceed inputs for very long because the stock of nutrient capital in the system will be depleted. When forests are burned, or the cut timber is removed as in logging, the nutrients that were in the tree biomass are either washed out in the case of burning or simply removed from the system. Because there was only a small stock of nutrients in the soil and most of the nutrients were in the biomass, there is little nutrient stock remaining to support regrowth of the forest. This is why slash and burn agriculture does not work for more than a few years after burning, and why the land is made very infertile and growing new vegetation is difficult. We can't simply "regrow" tropical rainforests once they are burned -- once they are lost they are gone forever (or at least for 1000s of years, and even then the species that regrow will be different from the original forest species).  Table 1 above shows 7 tropical forests, arranged roughly from least to most fertile soils. Note the range of above-ground biomass is about twofold. Yet the nutrient stocks vary by several orders of magnitude (an "order of magnitude" is equal to one power of ten, so that 100 is one order of magnitude greater than 10, and 1000 is two orders of magnitude greater than 10). The greatest above-ground productivity is in the Ivory Coast forest, on soils of intermediate fertility. This reinforces the point that you cannot guess the fertility of the soils of a tropical forest by looking at the productivity of the trees. Look next at the root biomass, which correlates pretty well with the soil fertility. Root biomass is highest where soil quality is poorest, and vice-versa. There is also a "causal" or mechanistic explanation for this correlation; when soil nutrients are high, the tree does not need to spend as much energy in building roots to forage in the soil for new nutrient sources. Competition for nutrients presumably is very strong at the Venezuelan sites with low soil fertility and high root biomass, whereas competition for light presumably is most important in the Ivory Coast forest. At the Venezuelan sites we have higher root biomass and there is well-developed surface root mat infiltrating the litter. We also see tougher, more slowly decaying leaves at the poor fertility sites. To see this in the data, note how the turnover time leaves, or how long a plant "holds on" to a leaf it has made, is around two years at the low nitrogen, high root mass sites (left side of the Table), and the turnover time of leaves is shorter and only around 1 year in the higher fertility soils (right side of the Table). This is because leaves are held longer under poor growth conditions (their turnover time is longer), and because they are exposed to herbivores longer they must be better protected (meaning they need to be tough and unpalatable). This causes slow decomposition of the leaves once they are dropped to the forest floor, and further retards the forest's productivity. Biodiversity Tropical forests, covering 7% of the earth's surface area, contain perhaps 50% of the world's species. What causes this prodigious concentration of biological diversity? Until ten years ago, if you had asked any biologist how many species of plants and animals lived on earth, the answer probably would have been "about 2 million." This would include the nearly 1.5 million described species, and allowed for another half million un-described species. | ||

Figure 6: Breeding bird species of North and Central America. Note that there is a general trend of increasing species diversity moving from higher latitudes toward to the tropics. | ||

| Then, in 1982, Smithsonian biologist Terry Erwin developed a technique to fumigate the crowns of individually selected forest trees with biodegradable pyrethrin (the same chemical in mosquito coils). A huge number of previously unknown spiders, insects, and other invertebrates came tumbling down onto tarps spread on the forest floor. Based on the high proportion of undescribed species, and the expectation that each tree species contains many host-specific species (species that live only in that host tree), our estimates of biological diversity have been drastically altered. One commonly hears the figures of 5 to 30 million species, but the truth is we don't know. In fact, we know more about the stars in the sky than we do about the species on Earth. We are certain that tropical forests contain a great many species, and most of these are unknown to science. We also know that the tropics are highly diverse based on evidence from well-studied groups, including the vertebrates and flowering plants. Whenever one compares the number of species along a latitudinal gradient (Figure 6), one observes a trend of increasing numbers of species towards the equator. Why are tropical forests so diverse? We only have partial answers, but they revolve around (1) the high ecological "specialization" found in the tropics, and (2) around the extent of geographic isolation over time in the tropics, including repeated environmental shifts due to climate change. Let's look first at the spectacular specialization we observe in tropical forests. Tropical species exhibit highly specialized ecological roles. However, this begs the question of how these species became so specialized and diverse, and here we turn to an evolutionary perspective that is related to the many niches associated with the high degree of diversity of habitats in the tropical forests. Let's examine two examples of the high degree of specialization found in tropical forests: (a) multi-layered forests, and (b)ecological specialization of bird feeding strategies. The tropical forests themselves are multi-layered. A temperate forest usually has two or three main layers. In an undisturbed forest the trees are fairly similar in height, there usually is some ground vegetation, and in between there may or may not be a shade-adapted middle layer. But tropical forests are vertically more complex (Figure 7), and as many as five distinct layers exist, although the strict distinctness of layers is arguable (that is, one layer "grades" into another layer).   Figure 8: Arboreal versus ground-dwelling mammals, day and night | ||

Figure 9: Bird guilds and ecological specialization (light bars for the tropics, dark bars for the temperate zone) | ||

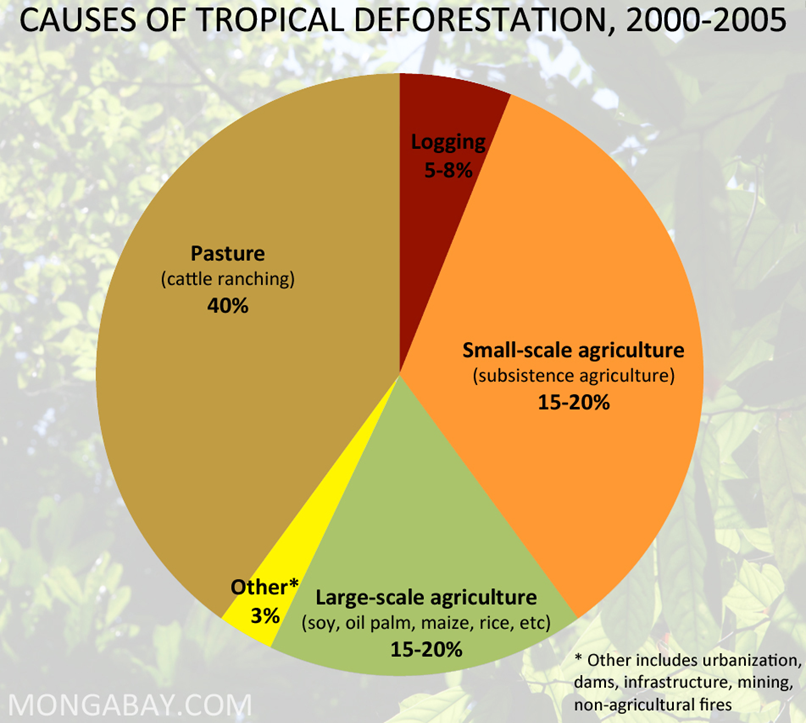

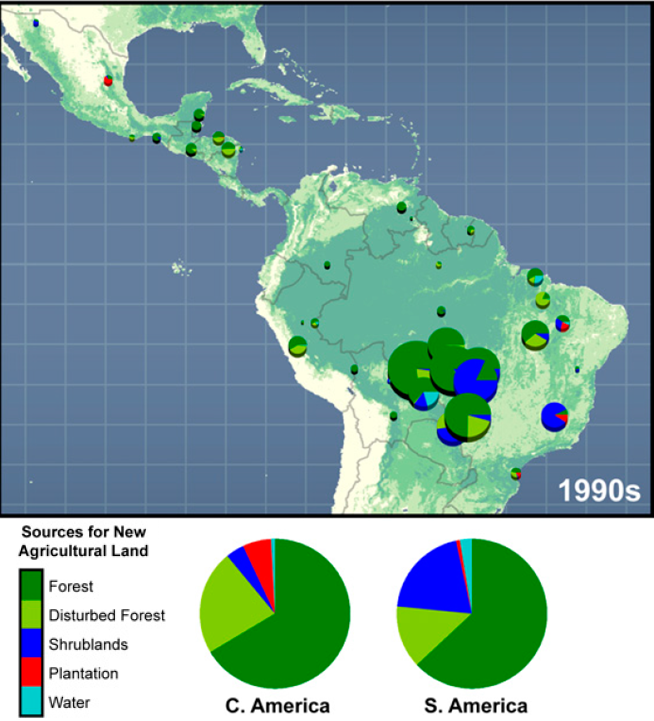

We also see evidence of great ecological specialization, as illustrated for mammals living in trees and on the ground that are active at day versus at night (Figure 8). The term "guild" is used in ecology much as it is used in human society, to describe a collection of individuals who make a living in the same way. Human examples include cobblers, brewers, and professors. In the animal kingdom we use the word guild to indicate a finer sub-division than trophic level. As Figure 9 illustrates for birds, there are more guilds in the tropics than in the temperate zone, and more species per guild in the tropics. Let's now turn to the deeper question of how this greater specialization came about. Although we don't fully understand why more species are formed in one place than another, we do know that geographical isolation of small populations for a long time promotes species formation (refer back to the Lecture on The Process of Speciation). This is because those isolated populations become independent genetic and hence independent evolutionary units. If the gene pool is small and the environment is unique, evolutionary specialization is likely. In South America, we know that before the rise of the Andes mountains, "Amazonia" once extended over most of northern South America. About 33 Ma ago (millions of anums), the breakup of the Pacific tectonic plates changed the geography and the Andes started uplifting. The Andes continued to rise with the main drainage toward the Atlantic Ocean to the northwest, but as the mountain building increased in the Central and Northern Andes (~12 Ma) there were more wetland areas developing in Western Amazonia. These different habitats, mountains and wetlands, facilitated allopatric speciation. In more recent times (say over the last 1-5 Ma), the forests of the tropics have gone through many cycles of fragmentation and reunion, due to the same global climate changes that gave us repeated bouts of glaciations at higher latitudes. These repeated episodes of forest retreat and advance would provide numerous opportunities for forest-dwelling species to be isolated into separate small populations. This in turn allows genetic change and evolutionary specialization to occur. The reasoning goes as follows. The border between forest and non-forest in present-day tropical South America closely follows the line of 1500 mm annual precipitation (Figure 10).  Figure 10: Contemporary pattern of rainfall in South America (left). On the right the dark blue shows areas that would have remained wetter during the times of glacial advance (drier times), and provided both refuges and geographic isolation for various species in the tropical forests. During wetter periods associated with interglacials (time during the glacial retreats), forests would expand and rejoin. If the dry periods correspond roughly to periods of glacial advance, they would have lasted 50 to 100 thousand years, which likely is sufficient time for evolutionary divergence. This process has happened over and over, in conjunction with the many cycles of glaciation that the Earth has experienced in the last several million years. Therefore the Milankovitch cycles , which drive much of the glacial activity, may have acted as a "species pump", causing the process of speciation to be more active in the tropics and resulting in more species found there today. Now, we must also remember that this idea is speculation because we cannot demonstrate the process in experiments and we can't go back in a time machine to observe the process directly. However, the process does correspond well to what we know about the causes of species formation, and how climate influences the distribution of dominant vegetation. There is evidence for this general idea of geographic isolation for birds in South American, but not for trees, while in Borneo (Indonesia) there appears to be evidence for this idea for trees, where glacial cycles have increased the isolation and potentially the speciation of forests. Some other factors probably contribute in part to the rich specialization of tropical rain forests. Two of the favored candidate factors are high year-round productivity, and the lack of any need to adapt to harsh environment conditions. In addition, specialization may favor further specialization, in a kind of runaway cycle. Human Use and SustainabilityTropical forests once covered 15-20% of earth's land surface. About half of this is now replaced by cropland, pasture, tree plantations, secondary forest, or wasteland. We are in a race between human destruction and human discovery. Some say we have less than 50 years before we'll hit bottom, with perhaps only 5-10% of tropical forests remaining. Why are we rapidly converting these lush, productive, and biologically diverse ecosystems to timber production, pasture land for cattle, and agriculture? Of course part of this conversion is to meet the needs for food and land of the rapidly growing number of peasant farmers in tropical countries (small-scale agriculture, Figure 11). However, much of the deforestation is being used for large-scale agriculture and ranching (e.g., 65-70% of land cut or burned is then used for cattle ranching in Brazil).

While there are clear needs to support local populations, the question is whether we are doing this in a sensible and sustainable way? Ecosystem science gives us a basis to evaluate this aspect of change now occurring on a global scale, using the criteria of productivity and ecological energy flow in relation to sustainability. 1. Disruption of nutrient cyclesTraditional slash and burn agriculture releases the nutrients held in above ground biomass to produce a high yield from a small area right after the burning. However, within 2-3 years these areas lose much of their productivity, because there are few nutrients available in the soils of tropical forests (the nutrients are in the biomass). Even if such areas are left fallow (unused) for years to decades, the productivity does not return because the nutrients have been mostly lost from the system, as described earlier in this lecture. This traditional land use is thus not "sustainable" because the majority of the land is fallow at any one time and new areas of forests must be cut and burned. The same issues apply to large-scale agriculture, and as we have learned in the Pollution and Great Lakes Climate Change lectures, simply adding fertilizers to soils has both an economic cost and an environmental cost in terms of nutrient runoff into surface waters.Alternatives to this agricultural system are highly debatable in terms of their sustainability and effect. There have been some spectacularly unsuccessful efforts to adapt modern agriculture from the temperate zone to tropical conditions. Without fertilizers, crop yields decline each year as the remaining nutrients in the soil are further depleted. Mechanization and fertilizers usually produce high yields, but the rate of soil erosion and degradation indicate that these practices are not sustainable into the future. High-tech agriculture also is costly and requires a level of technological sophistication that is inconsistent with the low-tech needs of rural agriculture. As a consequence, many people regard such efforts with great skepticism. However, research continues, and solutions would benefit people and simultaneously relieve some of the pressures on remaining wildlands.2. Disruption of the water cycleNot just nutrients are lost when the forest is removed. The water cycle itself is disrupted, and the initial consequence is increased erosion because there is no vegetation to act as a "buffer" to hold the water in the plants and soils. Another likely consequence is a long-term and irreversible decline in available water in the region. Initially in this lecture, we emphasized how climate determined the type of ecosystem in any tropical area, and thus its productivity. Here we see that ecosystems influence climate in the form of a feedback through the water cycle. An area as vast as the Amazonian rain forest recycles a great deal of rainfall back into the atmosphere by transpiration; in other words, the Amazon creates its own climate. If the forest is removed, that precipitation will run off to the sea via river flow, as has been demonstrated in many experiments where forests are clear cut. Evaporation of sea water will of course return fresh water to the atmosphere, but it is very unlikely that the Amazon rain forest will receive much of the rainfall. Without the transpiration of water from the trees back to the atmosphere in the region, the climate of the Amazon region will become drier, and it is questionable whether a humid tropical forest would ever be able to re-establish. Even if we could re-establish a wet tropical forest, experts now believe that the original biodiversity present will be impossible to regain. This general discussion about the water cycle in the Amazon has been supported by computer models in which the Amazonian forest was replaced by grasslands due to land use change. A consistent result in these models is that surface temperatures increase, evapotranspiration declines, and precipitation also declines. The simulations indicated that substantial dry season would occur, sufficient to prevent the re-establishment of a humid rainforest.Possible solutions One aspect of tropical deforestation is that the conversion of forest to agricultural or range land is being done more and more by large corporations instead of individuals, and in general it is easier to impose regulations on less sustainable practices on a corporation than on an individual. In addition, more and better understanding of species ranges may improve the outlook for conservation. For example, in the case of Borneo oranutans (which share 96.4% of our DNA), recent surveys show that only 22% of orangutan habitat is in protected areas or reserves. With more knowledge of where the orangutans live, new reserves can be better designed to incorporate critical habitat, and deforestation in areas of high orangutan occurrence could be restricted. Finally, although there are many "diagrams" and plans for decision making on saving tropical rainforests, too many of them don't incorporate basic scientific understanding into the plan to properly evaluate ecosystem function and services such as nutrient and water cycling, and to evaluate their overall sustainability. Summary

Review

Suggested ReadingsTerborgh, John. 1992. Diversity and the Tropical Rainforest. New York: Scientific American Library. 242 pp.

All materials © the Regents of the University of Michigan unless noted otherwise.

|

For further details log on website :

http://www.globalchange.umich.edu/globalchange1/current/lectures/kling/rainforest/rainforest.html

No comments:

Post a Comment