Published Date

Introduction

Producers and researchers are exploring many ways to address environmental sustainability and nuisance problems while adding value and improving transportability of manure to offset the costs of management practices. Manure management includes feed management, collection, transport, storage, handling, treatment, disposal and utilization of manure. This handbook will provide an introduction to agricultural composting and provide additional sources of information for those interested.

Composting is the biological decomposition and stabilization of organic material. The process produces heat that, in turn, produces a final product that is stable, free of pathogens and viable plant seeds, and can be beneficially applied to the land. As the product stabilizes, odours are reduced and pathogens eliminated. When composting high moisture materials, bulking materials are necessary for reducing moisture content and maintaining the integrity of the pile. Ideally, composting will enhance the usefulness of organic by-products as fertilizers, privately and commercially.

Composting is receiving increased attention as an alternative manure management practice due to increased pressures from society to reduce the impact on the environment. The producer may see alternative benefits to the reduction in volume of manure due to composting. Land base required to apply manure compost may stay the same but the producer can economically haul compost further than manure.

Table 1. Benefits and disadvantages of manure compost

The Composting Process

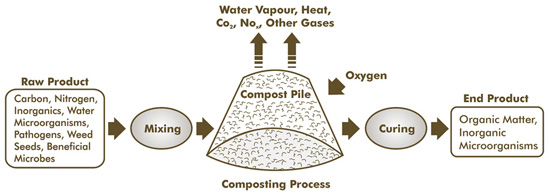

Under controlled conditions, composting is accomplished in two main stages: an active stage and a curing stage (Figure 1). In the active composting stage, microorganisms consume oxygen (O2) while feeding on organic matter in manure and produce heat, carbon dioxide (CO2) and water vapour. During this stage, most of the degradable organic matter is decomposed. A management plan is needed to maintain proper temperature, oxygen and moisture for the organisms. Testing temperature, moisture content, and oxygen levels can help make decisions on composting activities, such as turning, aerating, or adding moisture. These tests can be performed quite simply on site giving quick feedback - from minutes for temperature or oxygen to overnight for moisture content. In the curing phase, microbial activity slows down and as the process nears completion, the material approaches ambient air temperature. Finished compost takes on many of the characteristics of humus, the organic fraction of soil. The material will have been reduced in volume by 20 to 60%, the moisture content by 40% and the weight by up to 50%. One of the key challenges in composting is to retain as much nitrogen as possible. Composting may contribute to the greenhouse effect because carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (NH4) and nitrous oxide (NO2) will be emitted to the atmosphere during composting.

Figure 1. Material flow for the conventional composting process.

Factors Affecting the Composting Process

Controlling the process factors can accelerate the natural composting process. Each of these factors has the potential to significantly affect the composting process. Some of the important factors in the composting process are shown in Table 2 with their acceptable ranges.

Table 2. Factors affecting the composting process and acceptable ranges

Temperature

Temperature is a very good indicator of the process occurring within the composting material. The temperature increases due to the microbial activity and is noticeable within a few hours of forming a pile as easily degradable compounds are consumed. The temperature usually increases rapidly to 50 - 60°C (122 - 140°F) where it is maintained for several weeks. This is called the active composting stage. Biochemical reaction rates approximately double with each 10°C (50°F) increase in temperature, yet higher temperatures will increase ammonia loss during the composting process. The temperature gradually drops to 40°C (104°F) as the active composting slows down and the curing stage begins. Eventually, the temperature will become that of the surrounding air.

The highest rates of decomposition occur when temperatures are in the range of 43 - 66°C (110 - 150°F). During the active composting stage, the temperature may start to fall because of a lack of oxygen. Turning the material introduces new oxygen and the active composting stage continues. The temperatures can exceed 70°C (158°F) but many microorganisms begin to die, which stops the active composting stage. Cooling the material by turning helps to keep the temperature from reaching these damaging levels. Heat loss occurs primarily because of water evaporation from the material. Heat loss can also occur if the pile is too small or is exposed to cold weather. If the moisture content falls too low it increases the chance of obtaining damaging high temperatures.

The temperature should be maintained at 55°C (131°F) or higher for a minimum of 14 days to destroy the viability of many pathogens and weed seeds. Remember, the edges of the windrow are cool, therefore they must be turned into the center to kill the weed seeds.

The temperature can be measured with a one metre (three foot) long dial temperature probe.

Figure 2. Temperature measurement probe.

Carbon to Nitrogen Ratio

The carbon to nitrogen ratio (C:N) of manure is a very important factor that affects the whole composting process because microbes need 20 to 25 times more carbon than nitrogen to remain active. The ratio should be between 25:1 and 30:1 at the beginning. The microorganisms digest carbon as an energy source and ingest nitrogen for protein and reproduction. Softwood shavings, sawdust and straw are good sources of carbon. Other inexpensive sources of carbon include municipal waste and shredded newsprint or cardboard. Most manures are a good source of nitrogen but may be low in carbon depending on the amount of bedding used. Table 3, in this chapter, lists the C:N ratio for materials commonly included in farm compost. The content of materials on your farm can be estimated using the table or a laboratory can perform the analysis.

If the ratio is too high (insufficient nitrogen), the decomposition slows. If the ratio is too low (too much nitrogen), it will likely be lost to the atmosphere in the form of ammonia gas. This can lead to odour problems (refer to the troubleshooting table in the back of the manual for solutions). Most materials available for composting do not fit the ideal ratio so different materials must be blended. Proper blending of carbon and nitrogen helps ensure that composting temperatures will be high enough for the process to work efficiently and ensures other nutrients are available for microbes in adequate supply.

Aeration

The minimum desirable oxygen concentration in the composting material is 5%. Greater than 10% is ideal to avoid anaerobic conditions and high odour potential. Aeration adds fresh air in the center of the composting material. Rapid aerobic decomposition can only occur in the presence of sufficient oxygen. Aeration occurs naturally when air warmed by the compost rises through the material, drawing in fresh air from the surroundings at the base of the windrow. Initial mixing of materials usually introduces enough air to start composting. Porosity and moisture content affect air movement through the composting material. Regular mixing of the material, referred to as turning, enhances aeration in the composting material. Good aeration during composting will encourage complete decomposition of carbon (C) to carbon dioxide (CO2) rather than releasing carbon as methane (CH4). Too much aeration, however, can actually reduce the rate of decomposition by cooling the composting material and may cause the release of too much CO2. Excessive air flow can remove a lot of moisture. Another consequence of excessive aeration is ammonia loss, especially with high nitrogen (low C:N ratio) mixes. As the material dries out, more ammonia volatilizes and consequently, more nitrogen is lost.

The oxygen concentration can be measured with an oxygen probe. However, temperature provides an adequate indication of the process conditions. If the supply of oxygen is limited, the composting process slows and the temperature begins to fall. In this case the composting materials should be turned.

Moisture Content

Moisture plays an essential role in the metabolism of microorganisms and indirectly in the supply of oxygen. Microorganisms can utilize only those organic molecules that are dissolved in water. Moisture content between 50 and 60% (by weight) provides adequate moisture without limiting aeration. If the moisture content falls below 40%, bacterial activity will slow down and will cease entirely below 15%. When the moisture content exceeds 60%, nutrients are leached, porosity is reduced, odours are produced (due to anaerobic conditions) and decomposition slows. The squeeze test can be used to check the moisture content. The material is too wet if water can be squeezed out of a handful and too dry if the material doesn’t form a ball when squeezed.

Caution: Material in the pile will be very hot, use a shovel to remove material.

If the pile becomes too wet, it should be turned. This allows air to circulate back into it and loosens the materials for better draining and drying. Adding dry material, such as straw, sawdust or finished compost can also remedy excess moisture problems.

If the material is too dry, water can be added. An effective practice is to turn the material and rewet materials in the process. Shaping the pile can assist in shedding excess water from the pile. A windrow cover can be used to keep unwanted moisture from the elements out of the windrow and conserve moisture within the windrow. Optimum moisture content of raw materials should be between 50 and 60% (wet basis), depending on particle size, available nutrients and physical characteristics.

Porosity

Porosity refers to the spaces between particles in the compost material. These spaces are partially filled with air that can supply oxygen to the organisms and provide a path for air circulation. As the material becomes water saturated, the space available for air decreases, thus slowing the composting process.

Compacting the composting material reduces the porosity. Excessive shredding can also impede air circulation by creating smaller particles and pores. Turning fluffs up the material and increases its porosity. Adding coarse materials such as straw or woodchips can increase the overall porosity, although some coarse materials will be slow to decompose.

pH of Materials

The optimum pH for microorganisms involved in composting lies between 6.5 and 7.5. The pH of most animal manures is approximately 6.8 to 7.4. Composting alone leads to major changes in materials and their pH as decomposition occurs. For example, release of organic acids may, temporarily, lower the pH (increase acidity), and production of ammonia from nitrogenous compounds may raise the pH (increase alkalinity) during early stages of composting. On-site laboratory tests of pH can be used to maintain process control and product quality at a composting site.

Nutrients

Adequate levels of phosphorus (P), potassium (K), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), etc. are important in the composting process and are normally present in farm organic materials such as manure and livestock mortalities. Nutrient loss can occur through volatilization, losses to the atmosphere and leaching. Composting converts the nutrients in manure to stable forms that have a low ability to be lost by volatilization and leaching when applied to the land. However, during the composting process substantial amounts of nitrogen will be lost through ammonia volatilization. The ammonia emissions during composting reduce the fertilizer value of the finished compost. Nitrogen losses can also occur from emission of nitrous oxides or nitrogen gas.

Toxic Substances: CAUTION

Some organic materials may contain substances that are toxic to composting bacteria or bacteria required for composting. Heavy metals such as manganese, copper, zinc, nickel, chromium and lead fall into this category and may be immobilized chemically prior to composting. A laboratory can analyze samples of raw materials for toxic substances. Weathered fly ash, after equilibrating with atmospheric CO2, is called lagoon ash, which has an alkaline pH and provides a good fixing agent to suppress the availability of heavy metals in manure compost. Clopyralid is a long-lasting herbicide used to control broadleaf weeds. It does not pose a threat to humans or animals. It passes through animals and the composting process with little breakdown. Compost contaminated with clopyraid may harm certain types of broadleaf or ornamentals and vegetables such as beans, peas, peppers, tomatoes and potatoes. If you suspect that manure or compost is contaminated with clopyralid, it is better to send a manure or compost sample to the lab for testing.

Material Characteristics

It is important to be familiar with the material used in composting. Make sure to have proper C:N ratios. Materials can be blended together to attain the proper ratio. Table 3 contains characteristics of common on-farm composting materials. In order to blend materials in suitable proportions several factors must be considered. The necessary formulas and a sample calculation are in Appendix A.

Table 3. Characteristics of common composting materials

Composting Methods

As outlined in Table 4, some basic composting methods use bins, passive windrows, turned windrows, aerated static piles and in-vessel channels. The proper approach depends on the time to complete composting, the material and volume to be decomposed, space available, the availability of resources (labour, finances, etc.) and the quality of finished product required.

Table 4. Basic composting methods

Bin Composting

Bin composting is produced by natural aeration and through turning, using a tractor front-end loader. This option is primarily used for composting mortalities, yard waste and smaller amounts of manure. Operation and management of poultry and swine mortality compost systems are available from Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development.

Do stockpile ingredients, such as sawdust so it is available when needed.

Passive Windrow Composting

Passive windrow composting is the production of compost in piles or windrows by natural aeration over long periods of time. Attention to details such as the porosity of the initial mix, uniform product mixing and particle size greatly improve the speed of the process and product quality. Generally, material to be composted is collected and promptly piled into windrows, which remain untouched. The materials may be wetted before they are initially formed into windrows but this is not essential. Passive aeration has been successfully used in composting manure from poultry, dairy cattle and sheep.

Covering the windrow with a layer of finished compost will help to prevent moisture loss, reduce odour problems and produce more uniform compost. The center of a windrow will quickly become anaerobic and only by turning can it receive a new supply of oxygen. An unpleasant odour will develop in the anaerobic region and may begin to emanate from the composting material; hence, a large land area is necessary to buffer residents and businesses from the odour. Passive composting is not very conducive to oxygen presence. Since rapid composting can take place only in the presence of oxygen, the compost normally will require three years to stabilize.

Do use two windrows - build one while the other is decomposing undisturbed.

Don’t make the windrow too big (above six feet high) because this inhibits natural aeration and the material will take longer to compost.

Active Windrow Composting (Turned)

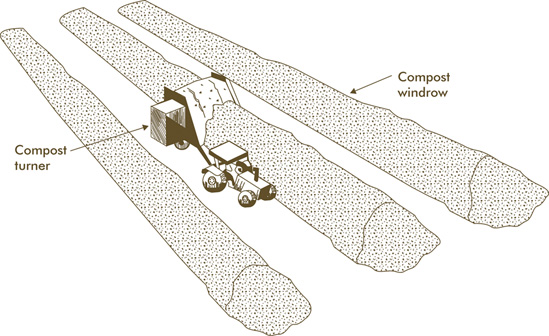

Active windrow composting is the production of compost in windrows using mechanical aeration by a front-end loader or a specially designed windrow turner. Loaders, although inexpensive compared to turners, have a tendency to compact the composting material, are comparatively inefficient, and can result in longer composting periods and less consistent quality. Turned windrow composting represents a low technology and medium labour approach and produces a uniform product.

The most commonly used windrow turners have a series of heavy tines that are placed along a rotating horizontal drum, which turns, mixes, aerates and reforms the windrow as the machine moves forward. These windrow turners are either self-contained units that straddle the row or are towed by a tractor and powered by a tractor PTO (Figure 3). The optimum height and width of the windrows depends on the type of equipment used to turn them.

Figure 3. Windrow turning with a pull-type turner.

Windrow composting can produce excellent compost using a variety of diverse materials. Wastes such as manure solids and paunch manure (offal), if in a secure compost area to eliminate scavengers, can be composted with bulking agents such as sawdust, straw and recycled paper products. Windrow composting efficiency and product quality are dependent primarily upon two major factors:

Don’t forget to check for lack of reheating after turning to signal the end of the active composting stage.

Aerated Static Pile Composting

Aerated static pile composting is the production of compost in piles or windrows with mechanical aeration and an air source such as perforated plastic pipes, aeration cones or a perforated floor. Aeration is accomplished either by forcing or drawing air through the compost pile. Aeration systems can be relatively simple using electrical motors, fans and ducting, or they can be more sophisticated incorporating various sensors and alarms.

This system of aeration requires electricity at the site and appropriate ventilation fans, ducts and monitoring equipment. The monitoring equipment determines the timing, duration and direction of airflow. The pile should be placed after the floors are first covered with a layer of a bulking agent, such as wood chips or finished compost. The material to be composted is then added and a topping layer of finished compost applied to provide insulation.

A major difficulty with the static pile system is the efficient diffusion of air throughout the entire pile, especially with wastes characterized by a large particle size distribution, high moisture content or a tendency to clump, such as dairy manure. Other problems include the formation of channels in the pile, which allow forced air to short-circuit. This causes excessive drying due to evaporation of moisture near the channels.

Do ensure materials chosen to compost have the proper porosity to prevent short-circuiting of air, such as dry wood chips.

Don’t assume that the airflow system provides adequate airflow uniformly.

In-Vessel Composting

In-vessel composting is the production of compost in drums, silos or channels using a high-rate controlled aeration system designed to provide optimal conditions. Aeration of the material is accomplished by:

Figure 4. In-vessel composting.

The main advantages of the in-vessel system over others are more efficient composting process and a decreased number of pathogens resulting in a safer and more valuable end product. In-vessel composting can maintain a rapid decomposition process year-round regardless of external ambient conditions. Disadvantages of the enclosed vessel method include high capital and operational costs due to the use of computerized equipment and skilled labour. In-vessel composters are generally more automated than active or static pile systems and can produce a top quality finished product on a consistent basis.

Do investigate the costs associated with building this type of facility.

Don’t forget that the materials need to be aerated by turning them.

Site Selection for Composting

If the production facility where the compost is to be made falls under the Agricultural Operation Practices Act (AOPA), contact the Natural Resources Conservation Board (NRCB) regarding site selection.

There are several factors to consider when choosing a composting site:

Space Requirements

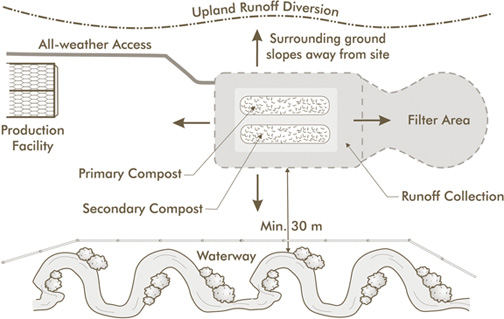

Appropriate separation or buffer distances between the composting operation and nearby water resources (surface and groundwater) and neighbouring homes can help to minimize the impact of any odour associated with raw materials, protect the water resources from possible contamination, and also meet the regulations.

Figure 5. General site layout recommendations for composting facilities.

Site Characteristics

There are both federal and provincial regulations governing compost. Both Alberta Environment and the Natural Resources Conservation Board (NRCB) are responsible for provincial regulations. The NRCB administers a one-window approach for confined feeding operations and for the compliance monitoring and enforcement of province-wide standards under the Agricultural Operation Practices Act (AOPA). On-farm manure composting is regulated by AOPA. Guidelines for locating compost facilities are found in Section 3 of the Standards and Administration Regulation of AOPA. Prior to setting up a composting facility, contact the NRCB to be advised on how the regulations affect you.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) Fertilizer Act regulates the sale of all compost in Canada. The label for both bagged and bulk sales of compost from any individual must comply with CFIA standards. Contact CFIA with the proposed labels prior to selling compost.

Compost Uses

Compost has numerous agronomic and horticultural uses. It can be used as a soil amendment, fertilizer supplement, top dressing for pastures and hay crops, mulch for homes and gardens, and a potting mix component. In these examples, the compost increases the water and nutrient retention of the soil, provides a porous medium for roots to grow in, increases the organic matter and decreases the bulk density or penetration resistance.

Troubleshooting

Table 5. Manure composting troubleshooting

Questions To Be Addressed Prior To Composting

For further details log on website :

http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/agdex8875

Introduction

Producers and researchers are exploring many ways to address environmental sustainability and nuisance problems while adding value and improving transportability of manure to offset the costs of management practices. Manure management includes feed management, collection, transport, storage, handling, treatment, disposal and utilization of manure. This handbook will provide an introduction to agricultural composting and provide additional sources of information for those interested.

Composting is the biological decomposition and stabilization of organic material. The process produces heat that, in turn, produces a final product that is stable, free of pathogens and viable plant seeds, and can be beneficially applied to the land. As the product stabilizes, odours are reduced and pathogens eliminated. When composting high moisture materials, bulking materials are necessary for reducing moisture content and maintaining the integrity of the pile. Ideally, composting will enhance the usefulness of organic by-products as fertilizers, privately and commercially.

Composting is receiving increased attention as an alternative manure management practice due to increased pressures from society to reduce the impact on the environment. The producer may see alternative benefits to the reduction in volume of manure due to composting. Land base required to apply manure compost may stay the same but the producer can economically haul compost further than manure.

Table 1. Benefits and disadvantages of manure compost

| Benefits | Disadvantages | |

|

|

The Composting Process

Under controlled conditions, composting is accomplished in two main stages: an active stage and a curing stage (Figure 1). In the active composting stage, microorganisms consume oxygen (O2) while feeding on organic matter in manure and produce heat, carbon dioxide (CO2) and water vapour. During this stage, most of the degradable organic matter is decomposed. A management plan is needed to maintain proper temperature, oxygen and moisture for the organisms. Testing temperature, moisture content, and oxygen levels can help make decisions on composting activities, such as turning, aerating, or adding moisture. These tests can be performed quite simply on site giving quick feedback - from minutes for temperature or oxygen to overnight for moisture content. In the curing phase, microbial activity slows down and as the process nears completion, the material approaches ambient air temperature. Finished compost takes on many of the characteristics of humus, the organic fraction of soil. The material will have been reduced in volume by 20 to 60%, the moisture content by 40% and the weight by up to 50%. One of the key challenges in composting is to retain as much nitrogen as possible. Composting may contribute to the greenhouse effect because carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (NH4) and nitrous oxide (NO2) will be emitted to the atmosphere during composting.

Figure 1. Material flow for the conventional composting process.

Factors Affecting the Composting Process

Controlling the process factors can accelerate the natural composting process. Each of these factors has the potential to significantly affect the composting process. Some of the important factors in the composting process are shown in Table 2 with their acceptable ranges.

Table 2. Factors affecting the composting process and acceptable ranges

| Factor | Acceptable Range |

| Temperature | 54 – 60 °C |

| Carbon to Nitrogen ratio (C:N) | 25:1 – 30:1 |

| Aeration, percent oxygen | > 5% |

| Moisture Content | 50 – 60% |

| Porosity | 30 - 36 |

| pH | 6.5 – 7.5 |

Temperature

Temperature is a very good indicator of the process occurring within the composting material. The temperature increases due to the microbial activity and is noticeable within a few hours of forming a pile as easily degradable compounds are consumed. The temperature usually increases rapidly to 50 - 60°C (122 - 140°F) where it is maintained for several weeks. This is called the active composting stage. Biochemical reaction rates approximately double with each 10°C (50°F) increase in temperature, yet higher temperatures will increase ammonia loss during the composting process. The temperature gradually drops to 40°C (104°F) as the active composting slows down and the curing stage begins. Eventually, the temperature will become that of the surrounding air.

The highest rates of decomposition occur when temperatures are in the range of 43 - 66°C (110 - 150°F). During the active composting stage, the temperature may start to fall because of a lack of oxygen. Turning the material introduces new oxygen and the active composting stage continues. The temperatures can exceed 70°C (158°F) but many microorganisms begin to die, which stops the active composting stage. Cooling the material by turning helps to keep the temperature from reaching these damaging levels. Heat loss occurs primarily because of water evaporation from the material. Heat loss can also occur if the pile is too small or is exposed to cold weather. If the moisture content falls too low it increases the chance of obtaining damaging high temperatures.

The temperature should be maintained at 55°C (131°F) or higher for a minimum of 14 days to destroy the viability of many pathogens and weed seeds. Remember, the edges of the windrow are cool, therefore they must be turned into the center to kill the weed seeds.

The temperature can be measured with a one metre (three foot) long dial temperature probe.

Figure 2. Temperature measurement probe.

Carbon to Nitrogen Ratio

The carbon to nitrogen ratio (C:N) of manure is a very important factor that affects the whole composting process because microbes need 20 to 25 times more carbon than nitrogen to remain active. The ratio should be between 25:1 and 30:1 at the beginning. The microorganisms digest carbon as an energy source and ingest nitrogen for protein and reproduction. Softwood shavings, sawdust and straw are good sources of carbon. Other inexpensive sources of carbon include municipal waste and shredded newsprint or cardboard. Most manures are a good source of nitrogen but may be low in carbon depending on the amount of bedding used. Table 3, in this chapter, lists the C:N ratio for materials commonly included in farm compost. The content of materials on your farm can be estimated using the table or a laboratory can perform the analysis.

If the ratio is too high (insufficient nitrogen), the decomposition slows. If the ratio is too low (too much nitrogen), it will likely be lost to the atmosphere in the form of ammonia gas. This can lead to odour problems (refer to the troubleshooting table in the back of the manual for solutions). Most materials available for composting do not fit the ideal ratio so different materials must be blended. Proper blending of carbon and nitrogen helps ensure that composting temperatures will be high enough for the process to work efficiently and ensures other nutrients are available for microbes in adequate supply.

Aeration

The minimum desirable oxygen concentration in the composting material is 5%. Greater than 10% is ideal to avoid anaerobic conditions and high odour potential. Aeration adds fresh air in the center of the composting material. Rapid aerobic decomposition can only occur in the presence of sufficient oxygen. Aeration occurs naturally when air warmed by the compost rises through the material, drawing in fresh air from the surroundings at the base of the windrow. Initial mixing of materials usually introduces enough air to start composting. Porosity and moisture content affect air movement through the composting material. Regular mixing of the material, referred to as turning, enhances aeration in the composting material. Good aeration during composting will encourage complete decomposition of carbon (C) to carbon dioxide (CO2) rather than releasing carbon as methane (CH4). Too much aeration, however, can actually reduce the rate of decomposition by cooling the composting material and may cause the release of too much CO2. Excessive air flow can remove a lot of moisture. Another consequence of excessive aeration is ammonia loss, especially with high nitrogen (low C:N ratio) mixes. As the material dries out, more ammonia volatilizes and consequently, more nitrogen is lost.

The oxygen concentration can be measured with an oxygen probe. However, temperature provides an adequate indication of the process conditions. If the supply of oxygen is limited, the composting process slows and the temperature begins to fall. In this case the composting materials should be turned.

Moisture Content

Moisture plays an essential role in the metabolism of microorganisms and indirectly in the supply of oxygen. Microorganisms can utilize only those organic molecules that are dissolved in water. Moisture content between 50 and 60% (by weight) provides adequate moisture without limiting aeration. If the moisture content falls below 40%, bacterial activity will slow down and will cease entirely below 15%. When the moisture content exceeds 60%, nutrients are leached, porosity is reduced, odours are produced (due to anaerobic conditions) and decomposition slows. The squeeze test can be used to check the moisture content. The material is too wet if water can be squeezed out of a handful and too dry if the material doesn’t form a ball when squeezed.

Caution: Material in the pile will be very hot, use a shovel to remove material.

If the pile becomes too wet, it should be turned. This allows air to circulate back into it and loosens the materials for better draining and drying. Adding dry material, such as straw, sawdust or finished compost can also remedy excess moisture problems.

If the material is too dry, water can be added. An effective practice is to turn the material and rewet materials in the process. Shaping the pile can assist in shedding excess water from the pile. A windrow cover can be used to keep unwanted moisture from the elements out of the windrow and conserve moisture within the windrow. Optimum moisture content of raw materials should be between 50 and 60% (wet basis), depending on particle size, available nutrients and physical characteristics.

Porosity

Porosity refers to the spaces between particles in the compost material. These spaces are partially filled with air that can supply oxygen to the organisms and provide a path for air circulation. As the material becomes water saturated, the space available for air decreases, thus slowing the composting process.

Compacting the composting material reduces the porosity. Excessive shredding can also impede air circulation by creating smaller particles and pores. Turning fluffs up the material and increases its porosity. Adding coarse materials such as straw or woodchips can increase the overall porosity, although some coarse materials will be slow to decompose.

pH of Materials

The optimum pH for microorganisms involved in composting lies between 6.5 and 7.5. The pH of most animal manures is approximately 6.8 to 7.4. Composting alone leads to major changes in materials and their pH as decomposition occurs. For example, release of organic acids may, temporarily, lower the pH (increase acidity), and production of ammonia from nitrogenous compounds may raise the pH (increase alkalinity) during early stages of composting. On-site laboratory tests of pH can be used to maintain process control and product quality at a composting site.

Nutrients

Adequate levels of phosphorus (P), potassium (K), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), etc. are important in the composting process and are normally present in farm organic materials such as manure and livestock mortalities. Nutrient loss can occur through volatilization, losses to the atmosphere and leaching. Composting converts the nutrients in manure to stable forms that have a low ability to be lost by volatilization and leaching when applied to the land. However, during the composting process substantial amounts of nitrogen will be lost through ammonia volatilization. The ammonia emissions during composting reduce the fertilizer value of the finished compost. Nitrogen losses can also occur from emission of nitrous oxides or nitrogen gas.

Toxic Substances: CAUTION

Some organic materials may contain substances that are toxic to composting bacteria or bacteria required for composting. Heavy metals such as manganese, copper, zinc, nickel, chromium and lead fall into this category and may be immobilized chemically prior to composting. A laboratory can analyze samples of raw materials for toxic substances. Weathered fly ash, after equilibrating with atmospheric CO2, is called lagoon ash, which has an alkaline pH and provides a good fixing agent to suppress the availability of heavy metals in manure compost. Clopyralid is a long-lasting herbicide used to control broadleaf weeds. It does not pose a threat to humans or animals. It passes through animals and the composting process with little breakdown. Compost contaminated with clopyraid may harm certain types of broadleaf or ornamentals and vegetables such as beans, peas, peppers, tomatoes and potatoes. If you suspect that manure or compost is contaminated with clopyralid, it is better to send a manure or compost sample to the lab for testing.

Material Characteristics

It is important to be familiar with the material used in composting. Make sure to have proper C:N ratios. Materials can be blended together to attain the proper ratio. Table 3 contains characteristics of common on-farm composting materials. In order to blend materials in suitable proportions several factors must be considered. The necessary formulas and a sample calculation are in Appendix A.

Table 3. Characteristics of common composting materials

| Material |

Nitrogen (dry weight) (%)

|

C:N (dry weight)

|

Moisture Content (%)

|

Bulk Density @Moisture Content (kg/m3)

|

| Beef | ||||

| - Feedlot with bedding |

1.3

|

1.8

|

68

|

710

|

| Dairy | ||||

| - Solid manure handling |

1.7

|

18

|

79

|

710

|

| - Liquid slurry |

2.40 - 3.60

|

16

|

88 – 92

|

990

|

| - Solids separated from slurry |

1.45

|

23

|

77

|

650

|

| Pigs | ||||

| - Liquid slurry |

0.15 - 5.00

|

20

|

93 - 99

|

1000

|

| - Solids separated from slurry |

0.35 - 5.00

|

1.9

|

75 – 80

|

270 - 860

|

| Poultry | ||||

| - Broiler breeder layer |

3.6

|

10

|

46

|

470

|

| - Broiler litter |

4.7

|

15

|

25

|

330

|

| - Turkey litter |

4.2

|

14

|

33

|

380

|

| Horse Manure with Bedding |

1.40 - 2.30

|

22 - 50

|

59 – 79

|

725 - 960

|

| - with straw |

1.5

|

27

|

67

|

-

|

| - with shavings |

0.9

|

65

|

72

|

-

|

| Sheep Manure |

1.30 - 3.09

|

13 – 20

|

60 – 75

|

-

|

| Straw | ||||

| - general straw |

0.30 - 1.10

|

48 - 150

|

27-Apr

|

58 - 357

|

| - oat straw |

0.60 - 1.10

|

48 – 98

|

14

|

130 - 192

|

| - wheat straw |

0.30 - 0.50

|

100 - 150

|

10

|

135

|

| - barley straw |

0.75 - 0.78

|

-

|

18-Dec

|

-

|

| Legume Grass Hay |

1.80 - 3.60

|

15 – 19

|

10 – 30

|

-

|

| Cardboard |

0.1

|

563

|

8

|

154

|

| Leaves 0.50 |

1.3

|

40 – 80

|

38

|

60 - 80

|

| Paper |

0.20 - 0.25

|

127 – 178

|

18 – 20

|

130

|

| Sawdust |

0.06 - 0.80

|

200 – 750

|

19 – 65

|

207 - 267

|

| Woodwaste (Chips) |

0.04 - 0.23

|

15 – 40

|

264 - 368

|

Composting Methods

As outlined in Table 4, some basic composting methods use bins, passive windrows, turned windrows, aerated static piles and in-vessel channels. The proper approach depends on the time to complete composting, the material and volume to be decomposed, space available, the availability of resources (labour, finances, etc.) and the quality of finished product required.

Table 4. Basic composting methods

Bin

|

Passive Windrow

|

Active Windrow

|

Aerated Static Windrow

|

In-Vessel Channel

| |

| General | Low technology, medium quality. | Low technology, quality problems. | Active systems most common on farms. | Effective for farm and municipal use. | Large-scale systems for commercial applications. |

| Labour | Medium labour required. | Low labour required. | Increases with aeration frequency and poor planning. | System design and planning important. Monitoring needed. | Requires consistent level of management/product flow to be cost efficient. |

| Site | Limited land but requires a composting structure. | Requires large land areas. | Can require large land areas. | Less land required given faster rates and effective pile volumes. | Very limited land due to rapid rates and continuous operations. |

| Bulking Agent | Flexible. | Less flexible, must be porous. | Flexible. | Less flexible, must be porous. | Flexible. |

| Active Period | Range: 2 - 6 months | Range: 6 - 24 months | Range: 21 - 40 days | Range: 21 - 40 days | Range: 21 - 35 days |

| Curing | 30+ days | Not applicable. | 30+ days | 30+ days | 30+ days |

| Size: Height | Dependent on bin design. | 1 - 4 metres | 1 - 2.8 metres | 3 - 4.5 metres | Dependent on bay design. |

| Size: Width | Variable. | 3 - 7 metres | 3 - 6 metres | Variable. | Variable. |

| Size: Length | Variable. | Variable. | Variable. | Variable. | Variable. |

| Aeration System | Natural convection and mechanical turning. | Natural convection only. | Mechanical turning and natural convection. | Forced positive/negative airflow through pile. | Extensive mechanical turning and aeration. |

| Process Control | Initial mix or layering and one turning. | Initial mix only. | Initial mix and turning. | Initial mix, aeration, temperature and/or time control. | Initial mix, aeration, temperature and/or time control, and turning. |

| Odour Factors | Odour can occur, but generally during turning. | Odour from the windrow will occur. The larger the windrow the greater the odours. | From surface area of windrow. Turning can create odours during initial weeks. | Odour can occur, but controls can be used, such as pile insulation and filters on air systems. | Odour can occur. Often due to equipment failure or system design limitations. |

Bin Composting

Bin composting is produced by natural aeration and through turning, using a tractor front-end loader. This option is primarily used for composting mortalities, yard waste and smaller amounts of manure. Operation and management of poultry and swine mortality compost systems are available from Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development.

Do stockpile ingredients, such as sawdust so it is available when needed.

Passive Windrow Composting

Passive windrow composting is the production of compost in piles or windrows by natural aeration over long periods of time. Attention to details such as the porosity of the initial mix, uniform product mixing and particle size greatly improve the speed of the process and product quality. Generally, material to be composted is collected and promptly piled into windrows, which remain untouched. The materials may be wetted before they are initially formed into windrows but this is not essential. Passive aeration has been successfully used in composting manure from poultry, dairy cattle and sheep.

Covering the windrow with a layer of finished compost will help to prevent moisture loss, reduce odour problems and produce more uniform compost. The center of a windrow will quickly become anaerobic and only by turning can it receive a new supply of oxygen. An unpleasant odour will develop in the anaerobic region and may begin to emanate from the composting material; hence, a large land area is necessary to buffer residents and businesses from the odour. Passive composting is not very conducive to oxygen presence. Since rapid composting can take place only in the presence of oxygen, the compost normally will require three years to stabilize.

Do use two windrows - build one while the other is decomposing undisturbed.

Don’t make the windrow too big (above six feet high) because this inhibits natural aeration and the material will take longer to compost.

Active Windrow Composting (Turned)

Active windrow composting is the production of compost in windrows using mechanical aeration by a front-end loader or a specially designed windrow turner. Loaders, although inexpensive compared to turners, have a tendency to compact the composting material, are comparatively inefficient, and can result in longer composting periods and less consistent quality. Turned windrow composting represents a low technology and medium labour approach and produces a uniform product.

The most commonly used windrow turners have a series of heavy tines that are placed along a rotating horizontal drum, which turns, mixes, aerates and reforms the windrow as the machine moves forward. These windrow turners are either self-contained units that straddle the row or are towed by a tractor and powered by a tractor PTO (Figure 3). The optimum height and width of the windrows depends on the type of equipment used to turn them.

Figure 3. Windrow turning with a pull-type turner.

Windrow composting can produce excellent compost using a variety of diverse materials. Wastes such as manure solids and paunch manure (offal), if in a secure compost area to eliminate scavengers, can be composted with bulking agents such as sawdust, straw and recycled paper products. Windrow composting efficiency and product quality are dependent primarily upon two major factors:

- The initial compost mix.

- Management practices.

Don’t forget to check for lack of reheating after turning to signal the end of the active composting stage.

Aerated Static Pile Composting

Aerated static pile composting is the production of compost in piles or windrows with mechanical aeration and an air source such as perforated plastic pipes, aeration cones or a perforated floor. Aeration is accomplished either by forcing or drawing air through the compost pile. Aeration systems can be relatively simple using electrical motors, fans and ducting, or they can be more sophisticated incorporating various sensors and alarms.

This system of aeration requires electricity at the site and appropriate ventilation fans, ducts and monitoring equipment. The monitoring equipment determines the timing, duration and direction of airflow. The pile should be placed after the floors are first covered with a layer of a bulking agent, such as wood chips or finished compost. The material to be composted is then added and a topping layer of finished compost applied to provide insulation.

A major difficulty with the static pile system is the efficient diffusion of air throughout the entire pile, especially with wastes characterized by a large particle size distribution, high moisture content or a tendency to clump, such as dairy manure. Other problems include the formation of channels in the pile, which allow forced air to short-circuit. This causes excessive drying due to evaporation of moisture near the channels.

Do ensure materials chosen to compost have the proper porosity to prevent short-circuiting of air, such as dry wood chips.

Don’t assume that the airflow system provides adequate airflow uniformly.

In-Vessel Composting

In-vessel composting is the production of compost in drums, silos or channels using a high-rate controlled aeration system designed to provide optimal conditions. Aeration of the material is accomplished by:

- Continuous agitation using aerating machines which operate in concrete bays.

- Fans providing air flow from ducts built into concrete floors.

Figure 4. In-vessel composting.

The main advantages of the in-vessel system over others are more efficient composting process and a decreased number of pathogens resulting in a safer and more valuable end product. In-vessel composting can maintain a rapid decomposition process year-round regardless of external ambient conditions. Disadvantages of the enclosed vessel method include high capital and operational costs due to the use of computerized equipment and skilled labour. In-vessel composters are generally more automated than active or static pile systems and can produce a top quality finished product on a consistent basis.

Do investigate the costs associated with building this type of facility.

Don’t forget that the materials need to be aerated by turning them.

Site Selection for Composting

If the production facility where the compost is to be made falls under the Agricultural Operation Practices Act (AOPA), contact the Natural Resources Conservation Board (NRCB) regarding site selection.

There are several factors to consider when choosing a composting site:

Space Requirements

- The site must have sufficient area for the volume of manure to be composted and should have sufficient area for future expansion.

- Consideration should be given to the space required for operation of the equipment at the site.

- Take into account the impact on the farm residence and any neighbouring residences.

Appropriate separation or buffer distances between the composting operation and nearby water resources (surface and groundwater) and neighbouring homes can help to minimize the impact of any odour associated with raw materials, protect the water resources from possible contamination, and also meet the regulations.

Figure 5. General site layout recommendations for composting facilities.

Site Characteristics

- Choose the location that has compacted soil or an impervious surface to reduce the seepage of the nutrient into the groundwater.

- The site must be sloped between 2 to 4%.

- The site must have a moderate to well drained soil surface.

- The site must be visible and have an easy access to hauling and storage.

- The site must have a permanent water diversion that works to keep surface runoff away from compost storage areas.

- Placement of manure storage, stacking or composting area should be a safe distance from floodways, wells or springs.

There are both federal and provincial regulations governing compost. Both Alberta Environment and the Natural Resources Conservation Board (NRCB) are responsible for provincial regulations. The NRCB administers a one-window approach for confined feeding operations and for the compliance monitoring and enforcement of province-wide standards under the Agricultural Operation Practices Act (AOPA). On-farm manure composting is regulated by AOPA. Guidelines for locating compost facilities are found in Section 3 of the Standards and Administration Regulation of AOPA. Prior to setting up a composting facility, contact the NRCB to be advised on how the regulations affect you.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) Fertilizer Act regulates the sale of all compost in Canada. The label for both bagged and bulk sales of compost from any individual must comply with CFIA standards. Contact CFIA with the proposed labels prior to selling compost.

Compost Uses

Compost has numerous agronomic and horticultural uses. It can be used as a soil amendment, fertilizer supplement, top dressing for pastures and hay crops, mulch for homes and gardens, and a potting mix component. In these examples, the compost increases the water and nutrient retention of the soil, provides a porous medium for roots to grow in, increases the organic matter and decreases the bulk density or penetration resistance.

Troubleshooting

Table 5. Manure composting troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

| The inside of the windrow is dry | Not enough water | Add water when turning the windrow |

| Temperature is too high | 1. Low to moderate moisture | 1. Add more water and continue turning the windrow |

| 2. The windrow is too big | 2. Try to decrease the size of the windrow | |

| Temperature is too low | 1. Insufficient aeration | 1. Turn the windrow more frequently to increase the airflow |

| 2. Wet condition of the windrow | 2. Add more dry material | |

| 3. Low pH | 3. Add lime or wood ash and remix | |

| Ammonia odour | 1. High level of N (C:N ratio less than 20:1) | 1. Add high carbon material, such as sawdust, woodchips, or straw |

| 2. High pH | 2.Lower pH by adding acidic ingredients (leaves) or avoid adding more alkaline materials such as lime and wood ash | |

| Hydrogen sulphide odour | Windrow material is too wet and its temperature is too low | Add dry bulk material |

Questions To Be Addressed Prior To Composting

- Do you have enough manure on your farm to compost?

- Do you have a site appropriate for composting?

- What composting method is best suited for your operation?

- Do you have access to carbon amendments such as straw, woodchips, etc.?

- Will compost product be for on-farm use or for export off the farm?

- If your compost is for off-farm sales, do you have a marketing strategy?

- Is there a market for compost in your area?

For further details log on website :

http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/agdex8875

No comments:

Post a Comment