" For other uses, see Land (disambiguation),

"Landmass" redirects here. For the ambient album by Steve Roach, see Landmass (album),

"Dry land" redirects here. For other uses, see Land (disambiguation).

Land, sometimes referred to as dry land, is the solid surface of the Earth, that is not permanently covered by water. The vast majority of human activity occurs in land areas that support agriculture, habitat and various natural resources.

Some life forms (including terrestrial plants and terrestrial animals) have developed from predecessor species that lived in bodies of water.

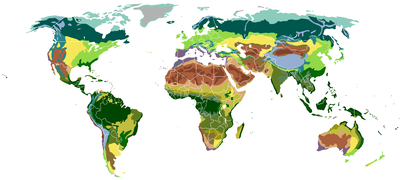

Map showing Earth's land areas, in shades of green and yellow

Areas where land meets large bodies of water are called coastal zones. The division between land and water is a fundamental concept to humans. The demarcation between land and water can vary by local jurisdiction and other factors. A maritime boundary is one example of a political demarcation. A variety of natural boundaries exist to help clearly define where water meets land. Solid rock landforms are easier to demarcate than marshy or swampy boundaries, where there is no clear point at which the land ends and a body of water has begun. Demarcation can further vary due to tides and weather.

Etymology and Terminology

The word 'land' is derived from Middle English land, lond and Old English land, lond (“earth, land, soil, ground; defined piece of land, territory, realm, province, district; landed property; country (not town); ridge in a ploughed field”), from Proto-Germanic *landą (“land”), and from Proto-Indo-European *lendʰ- (“land, heath”). Cognate with Scots land (“land”), West Frisian lân (“land”), Dutch land (“land”), German Land (“land, country, state”), Swedish land (“land, country, shore, territory”), Icelandic land (“land”). Non-Germanic cognates include Old Irish lann (“heath”), Welsh llan (“enclosure”), Breton lann (“heath”), Old Church Slavonic lędо from Proto-Slavic *lenda (“heath, wasteland”) and Albanian lëndinë (“heath, grassland”) from lëndë (“matter, substance”).

Rugged coastline of Knight's Point, New Zealand

A continuous area of land surrounded by ocean is called a "landmass". Although it may be most often written as one word to distinguish it from the usage "land mass" —the measure of land area—it is also used as two words. Landmasses include supercontinents, continents and islands. There are four major continuous landmasses of the Earth: Afro-Eurasia, Americas, Australia and Antarctica Land, capable of being ploughed and used to grow crops, is called arable land.

A country or region may be referred to as the motherland, fatherland, or homeland of its people. Many countries and other places have names incorporating -land (e.g. Iceland).

History of Land on Earth

The earliest material found in the Solar System is dated to 4.5672±0.0006 bya (billion years ago); therefore, the Earth itself must have been formed by accretion around this time. By 4.54±0.04 bya, the primordial Earth had formed. The formation and evolution of the Solar System bodies occurred in tandem with the Sun. In theory, a solar nebula partitions a volume out of amolecular cloud by gravitational collapse, which begins to spin and flatten into a circumstellar disk, which the planets then grow out of in tandem with the star. A nebula contains gas, ice grains and dust (including primordial nuclides). In nebular theory, planetesimals commence forming as particulate matter accrues by cohesive clumping and then by gravity. The assembly of the primordial Earth proceeded for 10–20 myr.

Earth's atmosphere and oceans were formed by volcanic activity and outgassing, that included water vapor. The origin of the world's oceans was condensation augmented by water and ice delivered by asteroids, proto-planets and comets. In this model, atmospheric "greenhouse gases" kept the oceans from freezing while the newly forming Sun was only at 70% luminosity. By 3.5 bya, the Earth's magnetic field was established, which helped prevent the atmosphere from being stripped away by the solar wind. The atmosphere and oceans of the Earth continuously shape the land by eroding and transporting solids on the surface.

Artist's impression of the birth of the Solar System

The crust, which currently forms the Earth's land, was created when the molten outer layer of the planet Earth cooled to form a solid mass as the accumulated water vapor began to act in the atmosphere. Once land became capable of supporting life, biodiversity evolved over hundreds of million years, expanding continually except when punctuated by mass extinctions.

The two models that explain land mass propose either a steady growth to the present-day forms or, more likely, a rapid growth early in Earth history followed by a long-term steady continental area. Continents formed by plate tectonics, a process ultimately driven by the continuous loss of heat from the Earth's interior. On time scales lasting hundreds of millions of years, the supercontinents have formed and broken apart three times. Roughly 750 mya (million years ago), one of the earliest known supercontinents, Rodinia, began to break apart. The continents later recombined to form Pannotia, 600–540 mya, then finally Pangaea, which also broke apart 180 mya.

Land Mass

"Land mass" refers to the total surface area of the land of a geographical region or country (which may include discontinuous pieces of land such as islands). It is written as two words to distinguish it from the usage "landmass", the contiguous area of land surrounded by ocean.

The Earth's total land mass is 148,939,063.133 km2 (57,505,693.767 sq mi) which is about 29.2% of its total surface. Water covers approximately 70.8% of the Earth's surface, mostly in the form of oceans and ice formations.

Cultural Perspective

Creation myths in many religions recall a story involving the creation of the world by a supernatural deity or deities, including accounts wherein the land is separated from the oceans and the air. The Earth itself has often been personified as a deity, in particular a goddess. In many cultures, the mother goddess is also portrayed as a fertility deity. To the Aztecs, Earth was called Tonantzin "our mother"; to the Incas. Earth was called Pachamama "mother earth". The Chinese Earth goddess Hou Tu is similar to Gaia, the Greek goddess personifying the Earth. Bhuma Devi is the goddess of Earth in Hinduism, influenced by Graha. In Norse mythology, the Earth giantess Jörð was the mother of Thor and the daughter of Annar. Ancient Egyptian mythology is different from that of other cultures because Earth (Geb) is male and sky (Nut) is female.

In the past, there were varying levels of belief in a flat Earth. The Jewish conception of a flat earth is found in both biblical and post-biblical times.

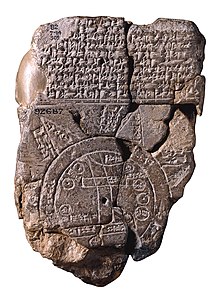

Imago Mundi Babylonian map, the oldest known world map, 6th century BC Babylonia.

In early Egyptian and Mesopotamian thought, the world was portrayed as a flat disk floating in the ocean. The Egyptian universe was pictured as a rectangular box with a north-south orientation and with a slightly concave surface, with Egypt in the center. A similar model is found in the Homeric account of the 8th century BC in which "Okeanos, the personified body of water surrounding the circular surface of the Earth, is the begetter of all life and possibly of all gods." The biblical earth is a flat disc floating on water.

The Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts reveal that the ancient Egyptians believed Nun (the ocean) was a circular body surrounding nbwt (a term meaning "dry lands" or "islands"), and therefore believed in a similar Ancient Near Eastern circular Earth cosmography surrounded by water.

The spherical form of the Earth was suggested by early Greek philosophers, a belief espoused by Pythagoras. Contrary to popular belief, most people in the Middle Ages did not believe the Earth was flat: this misconception is often called the "Myth of the Flat Earth". As evidenced by thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas, the European belief in a spherical, Earth Was widespread by this point in time. Prior to circumnavigation of the planet and the introduction of space flight, belief in a spherical Earth was based on observations of the secondary effects of the Earth's shape and parallels drawn with the shape of other planets.

Extraterrestrial Land

Most planets known to humans are either gaseous Jovian planets or solid terrestrial planets. Terrestrial planets include Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. These inner planets have a rocky surface with metal interiors. The Jovian planets consist of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. While these planets are larger, their only land surface is a small rocky core surrounded by a large, thick atmosphere. The gas giants, Jupiter and Saturn, are thought to have surface layers composed of liquid hydrogen rather than solid land; however, their planetary geology is not well understood. The possibility of Uranus and Neptune (the ice giants) possessing hot, highly compressed, supercritical water under their thick atmospheres has been hypothesised. While their composition is still not fully understood, a 2006 study by Wiktorowicz et al. ruled out the possibility of such a water "ocean" existing on Neptune, though some studies have suggested that exotic oceans of liquid diamond are possible. The entire surface of a rocky planet or moon is considered land, even with a lack of seas or oceans for contrast. Planetary bodies that have a thin atmosphere often have land that is marked by impact craters since atmospheric conditions would normally break-down incoming objects and erode rough impact sites. Land on planetary bodies other than Earth can also be bought and sold although ownership of extraterrestrial real estate is not recognized by any authority.

Land and Climate

The land of the Earth interacts with and influences climate heavily since the surface of the land heats up and cools down faster than air or water. Latitude, elevation, topography, reflectivity and land use all have varying impacts. The latitude of the land will influence how much solar radiation reaches the surface. High latitudes receive less solar radiation than low latitudes. The height of the land is important in creating and transforming airflow and precipitation on Earth. Large landforms, such as mountain ranges, divert wind energy and make the air parcel less dense and able to hold less heat. As air rises, this cooling effect causes condensation and precipitation. Reflectivity of the earth is called planetary albedo and the type of land cover that receives energy from the sun has an impact on the amount of energy that is reflected or transferred to Earth. Vegetation has a relatively low albedo meaning that vegetated surfaces are good absorbers of the sun’s energy. Forests have an albedo of 10-15% while grasslands have an albedo of 15-20%. In comparison, sandy deserts have an albedo of 25-40% Land use by humans also plays a role in the regional and global climate. Densely populated cities are warmer and create urban heat islands that have effects on the precipitation, cloud cover, and temperature of the region.

Notes

- ^ The picture of the universe in Talmudic texts has the Earth in the center of creation with heaven as a hemisphere spread over it. Biblical writings, such as the Genesis creation story and the various Psalms that extol the firmament, the stars, the sun, and the earth, give similar explanations. The Hebrews saw the earth as an almost flat surface consisting of a solid and a liquid part and the sky as the realm of light in which heavenly bodies move. The earth rested on cornerstones and could not be moved except by Jehovah (as in an earthquake). According to the Hebrews, the sun and the moon were only a short distance from one another. "Cosmology." Encyclopedia Americana. Grolier Online, 2012. Author: Giorgio Abetti, Astrophysical Observatory of Arcetri-Firenze.

- ^ The Earth is usually described as a disk encircled by water. Cosmological and metaphysical speculations were not to be cultivated in public nor were they to be committed to writing. Rather, they were considered to be "secrets of the Torah not to be passed on to all and sundry" (Ketubot 112a). While study of God's creation was not prohibited, speculations about "what is above, what is beneath, what is before, and what is after" (Mishnah Hagigah: 2) were restricted to the intellectual elite. (Topic Overview: Judaism, Encyclopedia of Science and Religion, Ed. J. Wentzel Vrede van Huyssteen. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2003. p477-483. Hava Tirosh-Samuelson).

References

- ^ Michael Allaby, Chris Park, A Dictionary of Environment and Conservation (2013), page 239, ISBN 0199641668.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed. "arable, adj. and n." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013.

- ^ Bowring, S.; Housh, T. (1995). "The Earth's early evolution". Science 269 (5230): 1535–40. Bibcode: 1995Sci...269.1535B. doi:10.1126/science.7667634 PMID 7667634.

- ^ See:

- Dalrymple, G.B. (1991). The Age of the Earth. California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1569-6.

- Newman, William L. (2007-07-09). "Age of the Earth" Publications Services, USGS. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved". Geological Society, London, Special Publications 190 (1): 205–221. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.190..205 . doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- Stassen, Chris (2005-09-10). "The Age of the Earth. TalkOrigins Archive. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ Yin, Qingzhu; Jacobsen, S. B.; Yamashita, K.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Télouk, P.; Albarède, F. (2002). "A short timescale for terrestrial planet formation from Hf-W chronometry of meteorites". Nature 418 (6901): 949–952. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..949Y. doi:10.1038/nature00995. PMID 12198540.

- ^ Morbidelli, A.; et al. (2000). "Source regions and time scales for the delivery of water to Earth". Meteoritics & Planetary Science 35 (6): 1309–1320. Bibcode:2000M&PS...35.1309M, doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2000.tb01518.

- ^ Guinan, E. F.; Ribas, I. "Our Changing Sun: The Role of Solar Nuclear Evolution and Magnetic Activity on Earth's Atmosphere and Climate". In Benjamin Montesinos, Alvaro Gimenez and Edward F. Guinan. ASP Conference Proceedings: The Evolving Sun and its Influence on Planetary Environments. San Francisco: Astronomical Society of the Pacific. Bibcode:2002ASPC..269...85G. ISBN 1-58381-109-5.

- ^ Staff (March 4, 2010). "Oldest measurement of Earth's magnetic field reveals battle between Sun and Earth for our atmosphere" Physorg.news. Retrieved 2010-03-27.

- ^ NOAA. Ocean Literacy.

- ^ Sahney, S., Benton, M.J. and Ferry, P.A. (2010). "Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land"(PDF). Biology Letters 6 (4): 544–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024. PMC 2936204. PMID 2010685.

External Links

- International Association of Geomorphologists.

- PhysicalGeography.net educational website.

- Wikipedia