Welcome back! If you like what you've been reading,

subscribe here to get new posts sent to you.

The Petropolis of Tomorrow, edited by Neeraj Bhatia and Mary Casper

The Petropolis of Tomorrow, edited by Neeraj Bhatia and Mary Casper

Off the coast of Brazil, dozens of floating oil rigs mark the first wave of an enormous boom in offshore oil extraction, with 45,000 workers already deployed offshore and more on the way. 70,000 helicopter trips every month ferry workers to and from the mainland. In the coming years, in order to service the drilling operations, the oil industry is expecting to build up to 50 new deep-water platforms, floating far beyond helicopter range. With this expansion, Brazil’s latent offshore oil industry is poised to shake up the region’s laws, economies and geopolitics, and to once again radically reshape the urban form of South America’s biggest nation and its capital city.

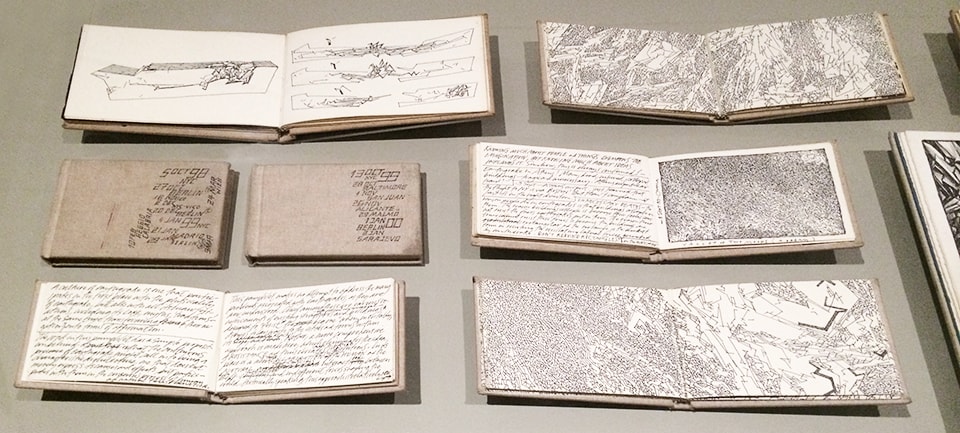

The Petropolis of Tomorrow focuses on the technologies, logics, logistics, and architectural possibilities of the floating mechanical islands that will serve this emerging oil boom. Edited by Neeraj Bhatia and Mary Casper, this ambitious book brings together critical essays by a number of architects and theorists, along with architectural projects, which are the products of design studios that Bhatia, now an Assistant Professor at California College of the Arts (CCA), ran at both Rice University and Cornell. Petropolis takes us on a historical and speculative exploration of oil frontiers, outposts, company towns, port cities, and artificial islands — as well as the lines of infrastructure, logistics, and capital that tie them together.

Bhatia is no stranger to infrastructure: as co-director of the research collective

InfraNet Lab, founder of

The Open Workshop, and co-editor of

Bracket [goes soft], his work has revolved around the larger speculative agenda of territory and infrastructure as it relates to architecture.

Can networks and logistics of extraction engender city making? And what does design offer to such places (and presumably the people who live and work there)?

Petropolis explores three main ideas — first, how the idea of floating cities opens up a way to think about architecture that moves beyond objects and towards networks; second, how the geography and use of vast territories take shape around the infrastructures of extraction and production; and third, how the logistics and technical realities of extraction and transmission imprint themselves on cities and landscapes, shaping land use and subsequent urban development. While the concepts may be heavy, the book explores them through a lush combination of photography, rich narrative, design provocations and critical theory and history — striving at once to introduce the reader to these striking landscapes, and to treat the critical topics with depth.

Throughout the book, several authors speculate on the tension between cities and company towns — asking whether infrastructure built for industrial purposes can form the foundation of actual urbanism, or whether any resultant urban form is doomed to a privatized and paternalistic existence under the parent company. To what extent is the territory off the coast of Brazil akin to the lawless frontier of the American West, which was so formative for American national identity, institutions, and individualism? What is the hidden imprint of oil on the form, location, and organization of towns? The essays and projects catalogued in Petropolis offer theoretical, historical, and speculative perspectives on the fundamental question of the book: Can networks and logistics of extraction engender city making? And what does design offer to such places (and presumably the people who live and work there)?

The book features grim yet stunning photoessays by Gareth Lenz, Alex Webb, and Peter Mettler, of oil extraction operations from the Caspean Sea to Alberta, Canada.

Bhatia organizes the book into three sections: Archipelago Urbanism, Harvesting Urbanism, and Logistical Urbanism. Archipelago Urbanism tackles the theoretical formulation of the polycentric network — the island archipelago as conceptual framework — and this idea’s role in architectural theory. The second section, Harvesting Urbanism, speculates on offshore production — farming, fisheries, aquaculture — and lends a deeper reading to a maritime territory that at first glance appears featureless and undifferentiated. Marine ecology of the offshore oil territory features prominently, with several essays focusing on the potential symbiosis between oil rigs and fisheries. The last section, Logistical Urbanism, tackles the logistical relationships between entities that manifest themselves as shipping routes, port hubs, components, plug-ins, lines of transmission and the corridors of ownership that shape them.

“In addition to searching for programmatic bands that might couple the primary technological objectives of the logistical easement, landscape and architectural design might offer ways to reveal the generative capacity of the logistical landscape, its massive temporal and scalar shifts, and the material displacements it effects.”

Brian Davis, Index of Landscape Typology: Easements

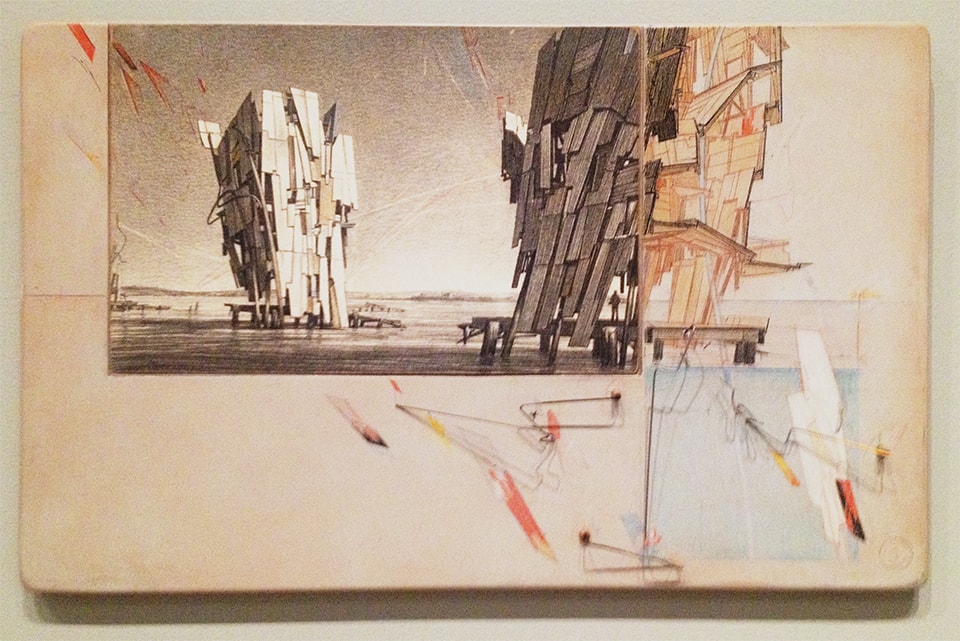

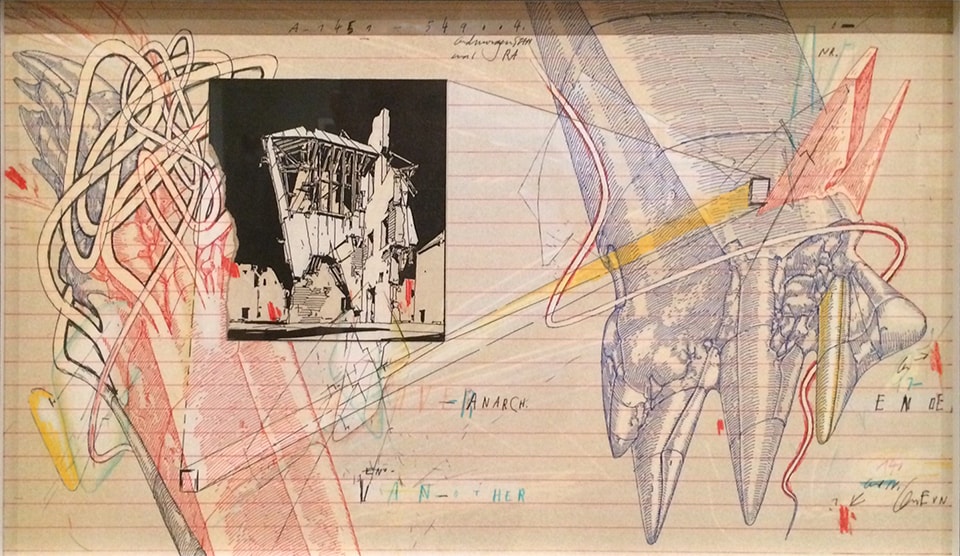

Each of the three sections is inaugurated by a lush photo-essay of an oil extraction operation, from the Alberta Tar Sands to the Caspian Sea, that gives us a taste of some of today’s most dramatic oil mining hotspots; each section concludes with a speculative architecture project offering a picture of futuristic floating cities that use the logistics of oil and gas extraction as “a backbone for more comprehensive urbanism at sea,” to quote from the Foreword by Felipe Correa. While the most interesting of the critical essays operate in the speculative historicism of cultural geography, the projects operate through polemical provocation, although subsequently developed into thoroughly detailed schematic schemes. These projects, arguing for the coupling of public or civic functions with the logistics of the oil rig in the Brazilian offshore territory, graft traditional urban typologies onto the new paradigm of collective offshore living: airport, civic center, shopping mall, workers’ housing. Other floating structures take on the production side of sea-based urbanism: agriculture, aquaculture, power plant, factory. Each is cleverly considered and satisfyingly rendered in a common graphic vocabulary; collectively they take the stance that architecture can remain specific while acting systemically — that the design of discrete nodes can produce larger urban patterns and functions.

Unlike the frontier town on land, however, the floating rig cities struggle to attract the diversity of economies and populations that might enable a true urbanism to flourish. Located so far offshore, they are isolated from one another and also from the casual flows of goods and people. While many of the projects attempt to critique and subvert the private company town model, they are most useful as provocations, as diagrams of challenges and opportunities, rather than as detailed designs for actual places. They grapple with the question, which Bhatia lays out in his Introduction, of whether the larger, richer, more powerful corporate and state entities that dominate the offshore oil game can be compelled to produce the bones of a truly viable urban construct.

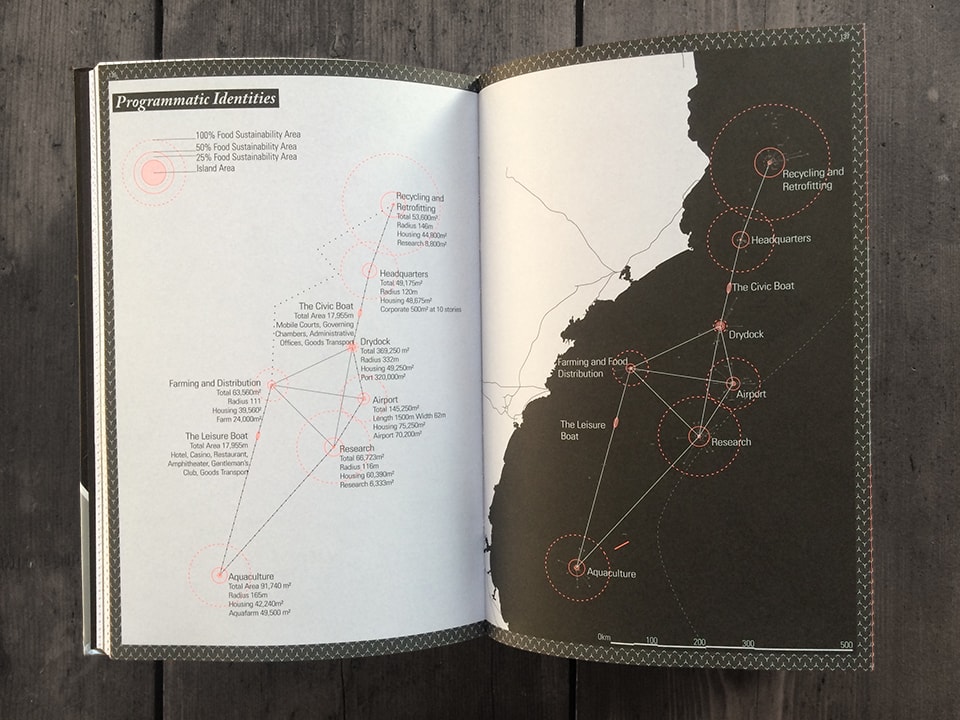

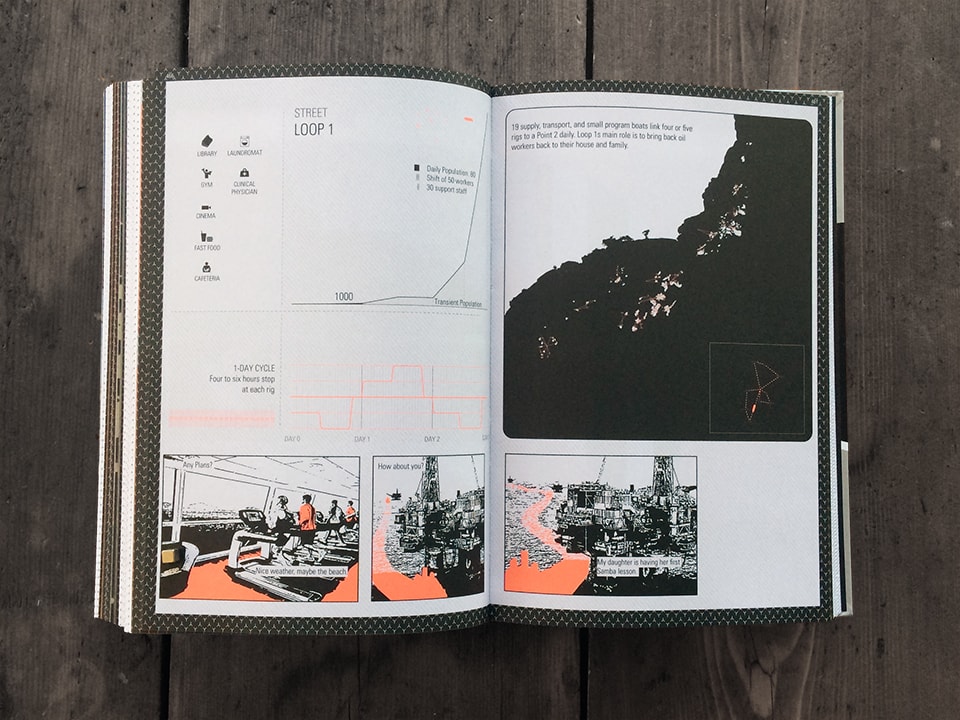

One of the more provocative projects proposes that a travelling “Civic Boat” visits the various offshore rigs in turn, providing needed social and law enforcement services, while establishing the island city as a municipality within the Brazilian federal government. Another project, recognizing that the density for true urbanism is lacking in any one rig, proposes to tie a spatially dispersed population of workers together through a temporal routine of mobile programs and events that sail between the scattered offshore outposts.

Programmatic identities of individual oil rigs, along with the itinerant “Civic Boat”

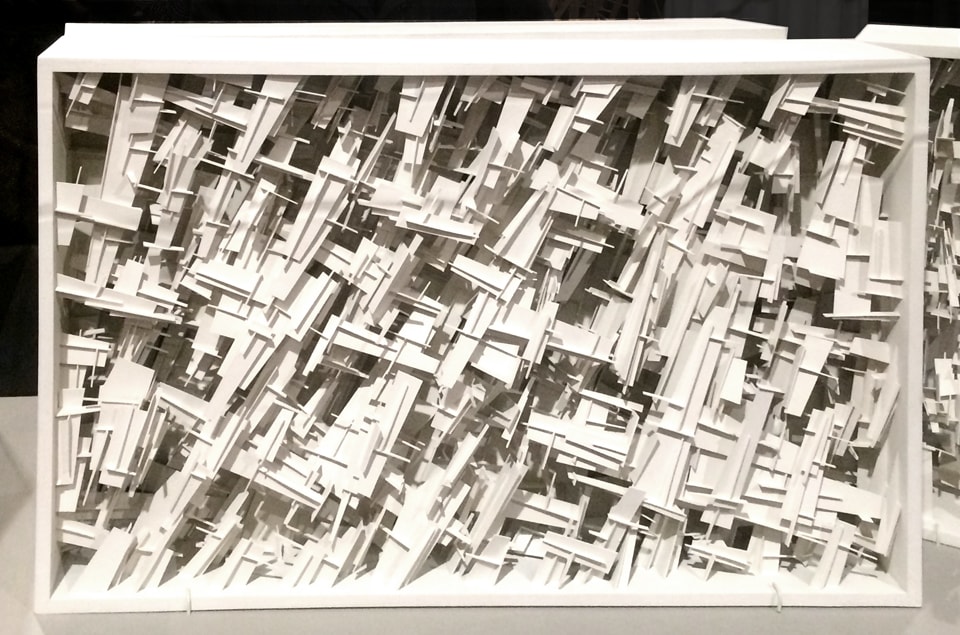

In many ways, the premise of floating cities is a wonderful proxy for the longstanding battle within architecture between a focus on the design of objects — autonomous exercises in form — versus that of networks, which are systemic, often invisible, and able to talk about larger logistical flows and operational relationships. The book unambiguously takes the stance of networks over objects, with numerous essays exploring the complex relationships between nodes in a system, interactions between the floating islands and the sea, and invisible lines of ownership and the physical manifestations of infrastructure. Several authors speculate on the organizational potential of archipelagos, a spatial construct that has been of interest for architects and urbanists since the 1970s, ever since Ungers’ and Koolhaas’ Berlin city-as-archipelago metaphor. Some argue for an update to this metaphor, expanding it to include the relationships between islands, as well as their differences. Others argue that the geological island metaphor needs to be merged with the biological metaphor of the organism in order to achieve an adequately operative complexity.

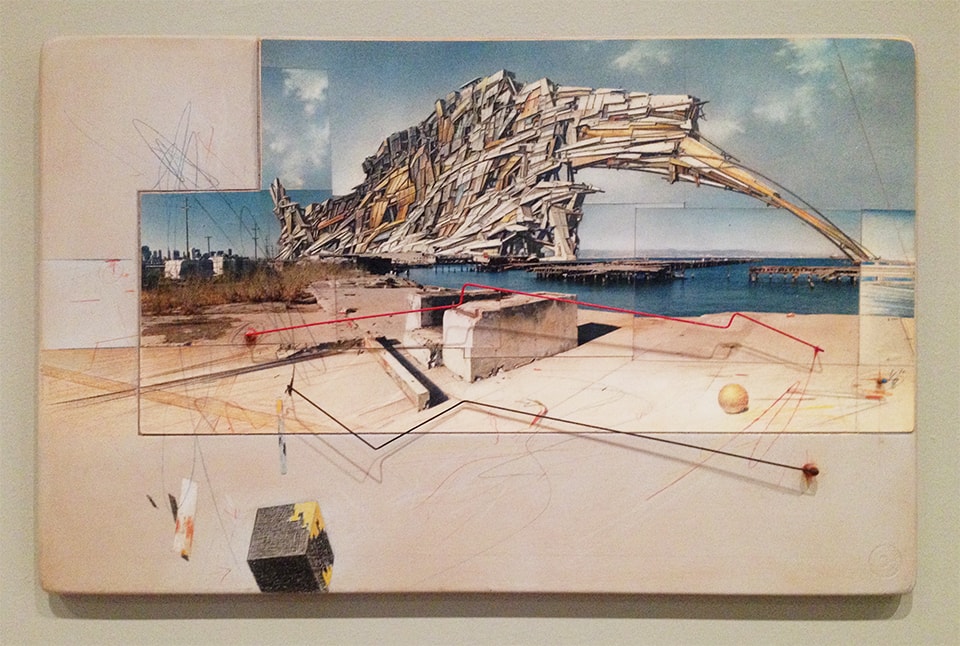

A floating drydock city, with public space for boats and people

But the deepest and most helpful pieces, from the point of view of elucidating the role of design upon the networked territory, are those that scrutinize the invisible patterns of the political and logistical landscape of oil extraction, which are critical for understanding the overall system at work.

“Although the oil territory is a landscape of lines, axes, nodes, points, blocks, and flows, the connectivity of such extensive spatial networks is rendered unevenly in its operations. The political reclamation of the offshore thus requires the examination of linkages and containments, continuities and discontinuities, as well as flows and frictions. It calls for a grounding of the offshore in a territorial project beyond the enclave of the rig.”

Rania Ghosn, The Expansion of the Extractive Territory

For Rania Ghosn, with her essay The Expansion of the Extractive Territory, the critical patterns are these invisible lines and flows. She points out that while the oil rig is the most visible technical piece of the oil extraction operation, it is the complex world of ownership, liability, and ecological and geological relationships that is critical for understanding oil extraction’s role on the territory. She argues for a representational agenda that can capture the full complexity — the “thick space” — of the offshore system. She also argues that the quest for resources is what has historically driven nations to explore and record their frontier territory, bringing “the state directly into contact with its territory — and more precisely with the qualities of this territory” for the first time. The process of extraction thus carries a larger representational agenda. Rather than focusing on the visible object floating on the water, she urges architects to engage with the qualities of the larger territory and its web of relationships, to make “the invisible visible,” and to uncover the power relationships that drive the system.

Similarly focusing on invisible yet powerful geographical structuring devices, Brian Davis points to the easement as a potent landscape typology operating at the scale of the territory, reshaping politics at both local and regional scales. He draws a helpful distinction between technological objects (such as the pipeline), and the easement that permits the deployment of the pipeline or transmission line (which negotiates between abstract lines and the specific terrain of the territory). The technological object is autonomous — responding to its own internal logic, carefully calibrated for its precise technical function. The easement, however, cuts a unifying swath across varied terrain, across conflicting ownerships, across biomes and habitats — opening up tantalizing potentials, in the way it is designed and detailed, to create entire new easement landscapes, coupling transmission with linear industries, new habitats, recreational systems, firebreaks, productive properties. The easements of pipelines, power lines, highways, and canals tie the city to its resource flows, extending the urban territory far beyond the city.

A worker’s routine, dispersed in space but ordered in time, across the offshore territory

The logistics and flows of oil, shipping, and capital determine where the physical infrastructures of industry get placed, but these in turn shape urban form. Several essays explore how pipelines, ports, refineries, and logistics hubs organize patterns of settlement far into the future. Carolina Hein’s essay describes how many port cities, energized as nodes in the larger network of petroleum shipping, carry frameworks of urbanism inscribed with the spatial logistics of oil. The massive oil infrastructure in these cities lingers long after the operations have moved on, presenting a challenge of reuse, but also an opportunity for comprehensive design and planning. And as Bhatia shows in his analysis of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline, it was the technological object that formed the kernel and the armature of settlement in a vast swath of the Arabian desert. Pump stations along the pipeline, with their water infrastructure, road access, medical and educational services, worker housing, mail and communications, gathered dispersed nomadic communities into permanent settlements in the desert that continue to grow to this day.

To what extent can the private interests that deploy these enormous infrastructures be compelled to care for the urbanistic or cultural needs of the places they will utilize? Rather than provide a single answer, the projects in Petropolis offer up a rich menu of ways to start thinking about questions about the boundary between private and public, about the role of design in an industry driven by economic gain, and about the relationship between object and system. In speculating on urbanism on such challenging and dispersed sites, Bhatia posits a way for architects to operate on both the technological system and the territory, using the geospatial, analytic and projective skillset of architectural urbanism.

But most importantly, The Petropolis of Tomorrow provides an opening salvo of writings on the operations, logic, and logistics of a massive petro-economic system that is morphing rapidly while continuing to drive both energy policy and geopolitics, and where too many designers fear to tread.