Published in Scenario 04: Building the Urban Forest

Spring 2014

Author

by Roxi Thoren

Roxi Thoren is an associate professor in the departments of architecture and landscape architecture at the University of Oregon. Prior to joining the UO, she practiced architecture and landscape architecture in Boston, Charlottesville, and Philadelphia. She is the author of Landscapes of Change, to be released in fall 2014, in which she examines innovative landscape architectural strategies that respond to new social and physical contexts. Professor Thoren is the Director of the UO’s Fuller Center for Productive Landscapes, which investigates the integration of productivity in landscape architecture design, including most recently a series of projects around forestry.

Roxi Thoren is an associate professor in the departments of architecture and landscape architecture at the University of Oregon. Prior to joining the UO, she practiced architecture and landscape architecture in Boston, Charlottesville, and Philadelphia. She is the author of Landscapes of Change, to be released in fall 2014, in which she examines innovative landscape architectural strategies that respond to new social and physical contexts. Professor Thoren is the Director of the UO’s Fuller Center for Productive Landscapes, which investigates the integration of productivity in landscape architecture design, including most recently a series of projects around forestry.

https://scenariojournal.com/article/deep-roots/

Spring 2014

Author

by Roxi Thoren

“The more you think about the services of the forest, the more you understand them, the more essential they appear. It is true indeed that the forest, rightly handled – given the chance – is, next to the earth itself, the most useful servant of man.”

– Gifford Pinchot [1]

For a brief period at the turn of the last century, landscape architecture and forestry occupied the same physical and conceptual space — the design of landscapes and the management of natural resources were inextricable. The work of Frederick Law Olmsted and Gifford Pinchot at Biltmore Estate in North Carolina in the 1890s represents the beginning of American forestry and a model of professional collaboration, as the founding figures of two professions used the design and management of the estate to test the viability of scientific land and resource management.

Olmsted, the preeminent American landscape architect at the close of the 19th century, proposed scientific forestry for much of the prestigious commission, and he hired Gifford Pinchot to implement his forest management plan on Biltmore’s eroded, wasted hillsides. Pinchot would go on to become the first chief of the United States Forest Service and governor of Pennsylvania, but at the time, he was a young man freshly trained in Europe in the scientific practice of forest management. Together, they created an expansive laboratory for land reclamation and land management. Their collaboration represented shared ideals and thinking about land and landscape, and their Biltmore work continues to inform both the practice and the discourse of forestry today.

Over the intervening century, the fields of landscape architecture and forestry have moved apart, following internal imperatives. Yet today, as both professions are re-examining forests, especially in urban contexts, there is an opportunity to recover the early collaboration of landscape architects and foresters and to integrate the two practices.

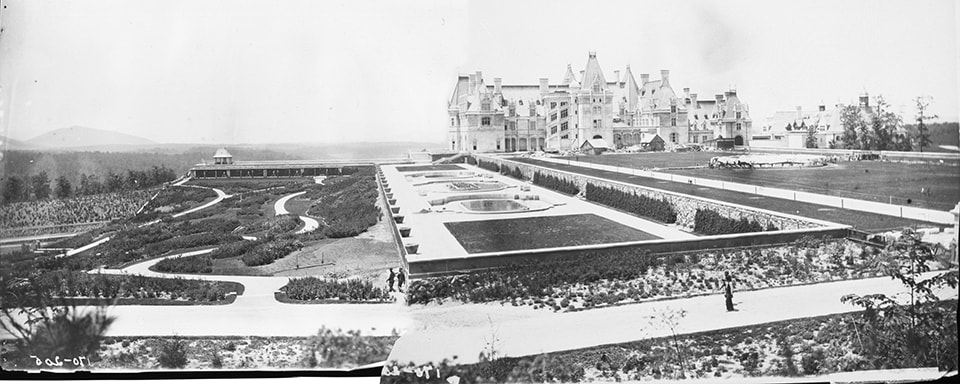

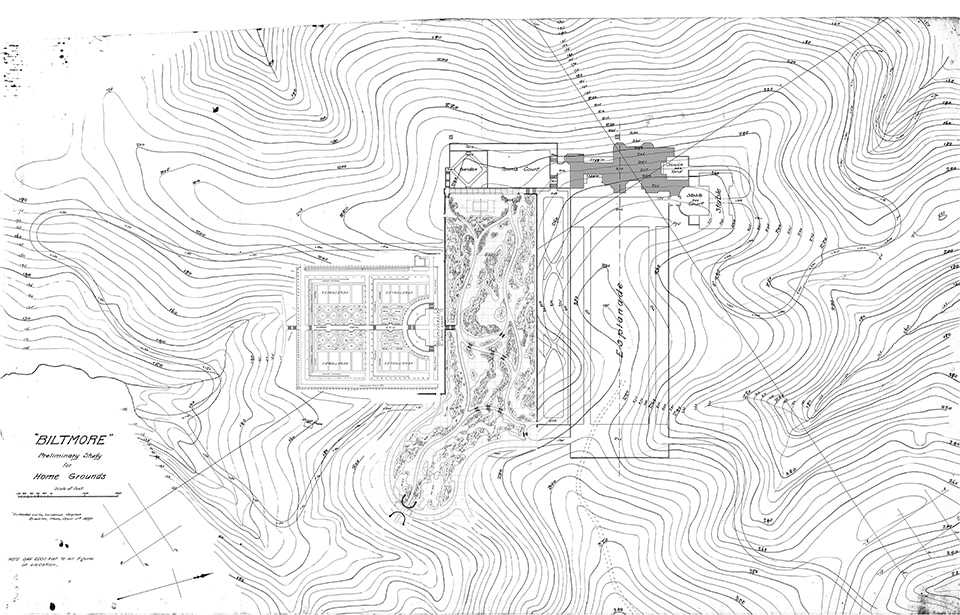

Biltmore house and the gardens: From north (right) to south (left): the esplanade, the water garden, the ramble, and barely visible below the slope, the productive garden, providing vegetables and flowers. A pine plantation is visible behind the productive garden. The gardens were intended to be a ”small park” and a “small pleasure ground and garden” – a clearing in the woods. (Images courtesy of the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site, collaged by author)

The Biltmore Estate

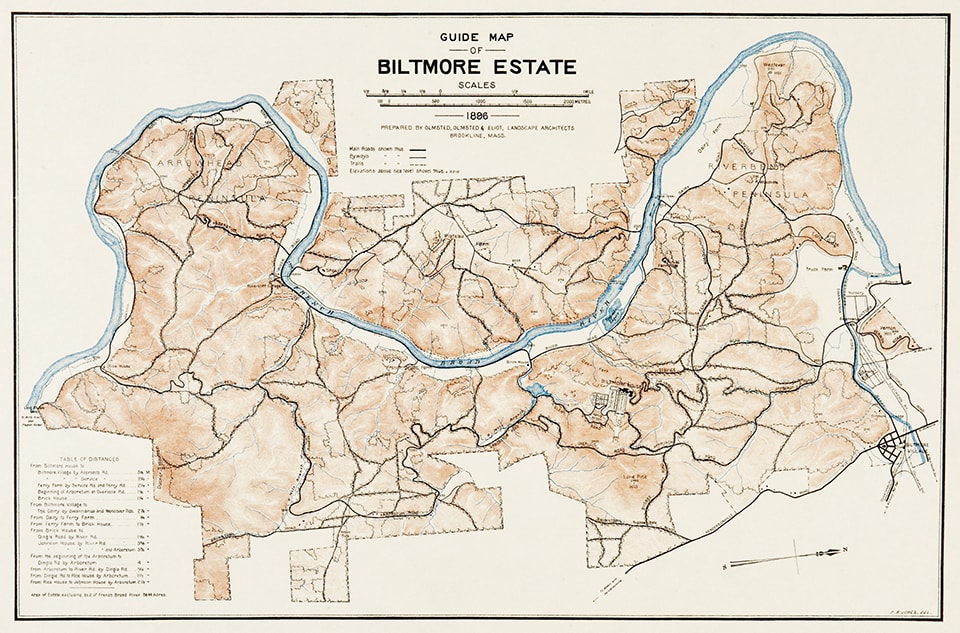

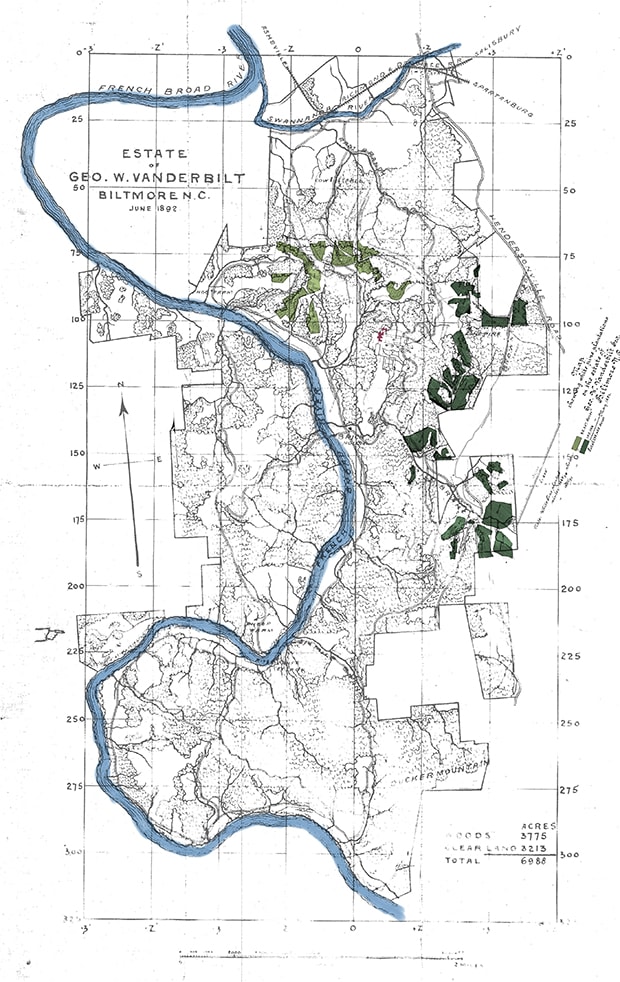

In 1888, George Washington Vanderbilt II began to assemble 6,000 acres of hilly land along the French Broad River, near Asheville, North Carolina, intending to create a French-style chateau surrounded by formal gardens and large parklands beyond. Vanderbilt intended Biltmore to be a true estate — self-supported by agriculture, timber, and other productive landscapes — and he hired Olmsted for the commission. At sixty-seven, Olmsted was the nation’s foremost landscape designer, and had significant experience in park and garden design as well as in scientific forestry and farming. At Biltmore, Olmsted found an exhausted landscape, severely degraded from previous uses, and he proposed forestry as a means of ecological restoration, material and economic productivity, recreation, and education. Olmsted advised his client,

“The soil seems to be generally poor. The woods are miserable, all the good trees having again and again been culled out and only runts left. The topography is most unsuitable for anything that can properly be called park scenery….Such land in Europe would be made a forest; partly, if it belonged to a gentleman of large means, as a preserve for game, mainly with a view to crops of timber. That would be a suitable and dignified business for you to engage in; it would, in the long run, be probably a fair investment of capital and it would be of great value to the country to have a thoroughly well organized and systematically conducted attempt in forestry made on a large scale. My advice would be to make a small park into which to look from your house; make a small pleasure ground and garden, farm your river bottom chiefly to keep and fatten live stock with a view to manure; and make the rest a forest, improving the existing woods and planting the old fields” [2].

The soils had been depleted from logging, fires to clear land, farming, and pasturing animals. Much of the steep land had eroded, and soils had washed away [3]. Olmsted proposed forestry to stabilize the land, improve the soils, provide profit for his client, and also provide a model of experimental forestry for the nation.

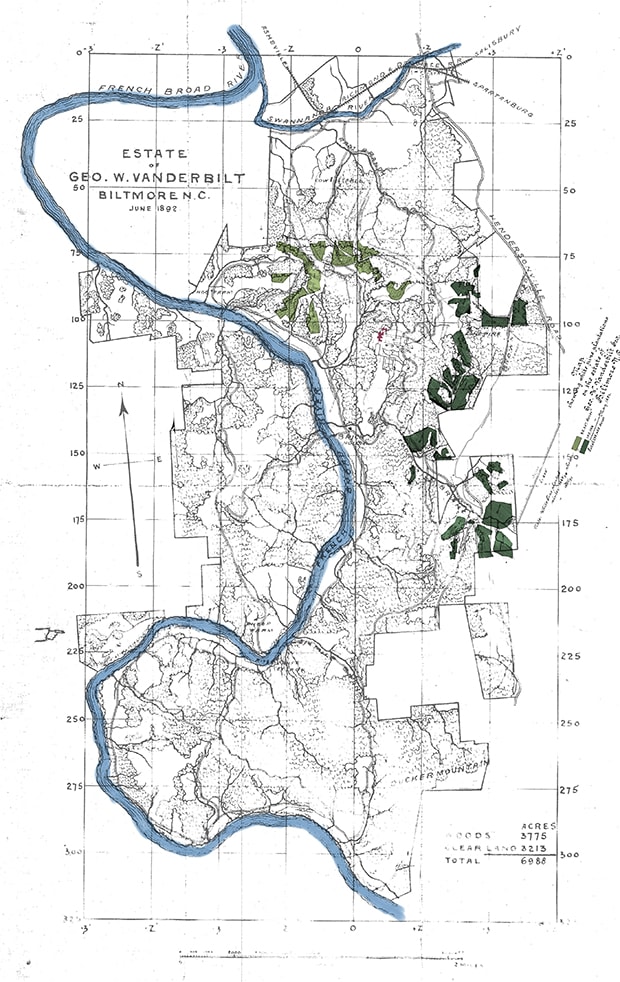

Plan of the Biltmore Estate in 1896: The house and gardens are middle right, and a 300-acre nursery is on the right (north) bank of the Swannanoa River (the smaller river on the north edge of the property). The majority of the property, then approximately 8,000 acres, was given to forestry. (Image courtesy of the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site)

Scientific Land Management

Throughout his career, Olmsted proposed landscape architecture as an ameliorative practice to improve the productivity of sites. He began his career as a scientific farmer, and proposed scientific forestry in California in the 1860’s. In the emerging profession of landscape architecture, Olmsted saw a need for rigorous scientific inquiry to ground the wise management of landscapes.

Biltmore was not Olmsted’s first forest commission, nor his first proposal for scientific land management. Rather, it was a chance to realize ideas that he began developing in Central Park, his first landscape design. In 1876, Olmsted wrote to the president of the Central Park Commission to propose that the park operate as a form of forestry laboratory. The first trees had been planted there eighteen years earlier, and Olmsted proposed recovering the weather conditions, maintenance regimes, and tree health for that period, and tracking that data into the future, saying that “it will be regarded as a matter of some national interest that such a record should be made and hereafter presented and continued. The Central Park would then form a Museum of Arboriculture arranged and catalogued suitably for profitable study” [4]. However, the park board did not act on Olmsted’s recommendation, and it would require private, not public lands for Olmsted to enact his vision of a national forestry laboratory.

In 1880, Olmsted designed Moraine Farm in Beverly, Massachusetts as a 275-acre scientific farm with a 75-acre experimental forest, both intended to advance an American mode of productivity. Over 60,000 larch, pine, spruce, and birch were planted as an experimental forest, determining which trees produced the best timber yields on degraded New England soils [5].

Private landownership meant that he could implement long-term projects, and design by cutting trees as well as planting. By 1889, about the time he began work on Biltmore, Olmsted had become so frustrated with his inability to effect scientific forestry in his large park projects that he wrote, with J. B. Harrison, Observations on the Treatment of Public Plantations, More Especially Related to the Use of the Axe, a pamphlet intended to educate the public on the necessity of thinning and removing trees.

The same year, in his report to Vanderbilt, Olmsted wrote, “as the undertaking now to be entered upon at Biltmore will be the first of the kind in the country to be carried on methodically, upon an extensive scale, it is even more desirable than it would otherwise be that it should, from the first, be directed systematically and with clearly defined purposes, and that instructive records of it be kept” [6]. Having witnessed visitors to Central Park attempt to “wrest the axe from the hand of the woodsman” in planned campaigns of thinning the thickly planted woods, planning a scientific forest on private lands must have seemed a rare opportunity to Olmsted [7].

Productive Pines: In 1892, the property encompassed approximately 7,000 acres. The light green shows pine plantations from the winter of 1889/90 (86 acres), dark green shows plantations from winter 1890/91 (169 acres). These plantations occurred before Pinchot was hired, and concentrated as they are in the viewshed of the house, they seem to be both ameliorative (for the soil) as well as aesthetic, creating the sense of a clearing in the woods. (Images courtesy of the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site, collaged by author)

Gifford Pinchot, the man Olmsted selected to oversee forestry at Biltmore, was at the time a young and inexperienced forester; the first (and at the time only) U.S.-born, trained forester; an ambitious twenty-six year old with a national vision for forest productivity and conservation. Pinchot saw a lax attitude in the United States towards natural resources, and he championed the nascent conservation movement, calling for governmental protection, on the European model, of natural resources from corporate abuse.

By 1890, Pinchot had studied forestry for a year at the École Nationale Forestière, in Nancy, France, and had spent months observing the forestry works in the Sihlwald forest in Zurich and on a tour of German forests led by one of the world’s preeminent foresters, Dietrich Brandis. His observations of the Sihlwald and on European forest policy had been published in Garden and Forest; although young, he was one of the nation’s leading experts on forestry [8].

Pinchot’s father James was a friend of Frederick Law Olmsted. Both were members of the same social clubs and professional associations, and they shared an interest in forestry [9]. Knowing of the work at Biltmore, James encouraged Gifford to apply to Olmsted for the position of forest manager; Gifford familiarized himself with the property, and approached Olmsted with preliminary suggestions for the land. In December 1891, Pinchot was hired to oversee the forest at Biltmore.

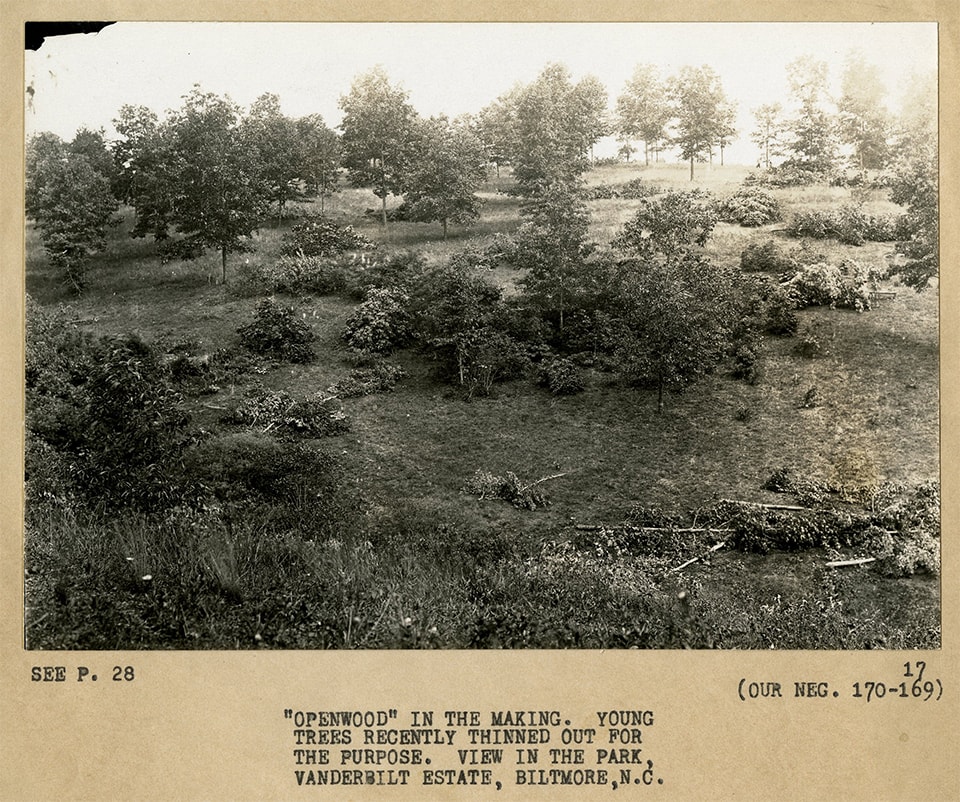

Forestry at Biltmore included both selective thinning of extant forests and planting in open fields. Here, young trees have been thinned for an open wood. (Image courtesy of the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site)

The Biltmore Forest Proposal

Pinchot intended a steady yield of timber from the forest. At the time, wood was needed for heating, for industrial furnaces, for fence, wagon, and building construction, for road and railroad construction, and for naval shipbuilding. American forests were being rapidly consumed for construction, for fuel, for development, for agriculture. Pinchot had toured forests in thirty-three states, and seen what he later described as the “absolute devastation” of most logging practices, which reflected the common perception of forests as having a single use — timber — and extracted the greatest one-time value from them, without considering either the time required to get the forests to their then-current state, nor made any provisions for their future growth [10].

America needed forests that could produce dependable, sustainable yields of timber. Pinchot also saw the need for synthetic forestry that expanded beyond simple timber benefits. His approach was grounded in resource conservation, and took nature as its guide. This was perhaps learned from Brandis, whose mid-nineteenth-century forestry has been called “proto-ecological,” as he understood the forest as an environment, with links between species and disturbance events [11]. Pinchot used this ecological approach in his own work; he saw a healthy forest as one with a broad distribution of tree ages, with trees close enough together that they would encourage straight growth, but far enough apart that they could be felled. Pinchot’s improvements and harvesting techniques were inspired by nature. Group cuts mimicked blowdowns, a natural form of clearing in the wood that encouraged young trees to sprout. Linear cuts mimicked tornadoes, but were limited in length to protect the forest, and typically ran east-west to minimize drying the forest floor.

At Biltmore, Pinchot sought to prove that logging and forest management were not incompatible, and that productive forestry could be profitable. His three goals for the Biltmore forests were to generate profit; be self-sustaining; and improve the health of the forest. He proposed a phased plan, first improving the existing forests by thinning poor stands, promoting natural regeneration and fencing out livestock that grazed on young trees, along with extensive planting. The first, poor-quality harvests would occur over six years, with an eventual 150-year harvest cycle that used a hybrid of two traditional forestry practices — high-forest harvest and selective harvest.

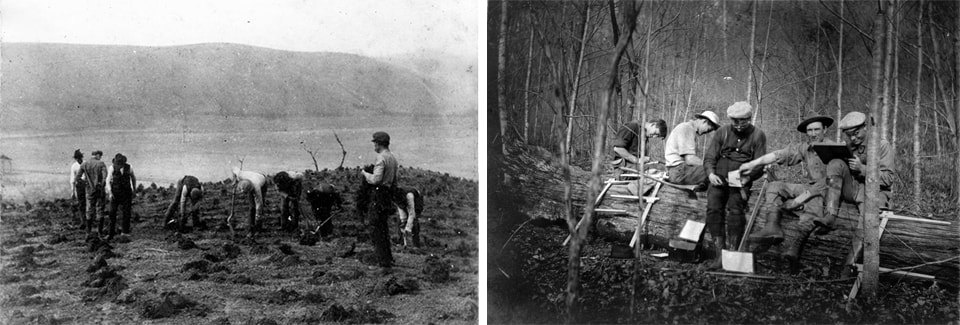

In high-forest harvest, land was divided into sections equal in number to the number of years for mature harvest. Each section contained even-aged trees, and the sections were sequentially harvested and replanted, with harvest returning to the first section after the prescribed number of years. In selective harvest, the entire forest was logged annually, felling only those trees of sufficient maturity. The latter method was more difficult, in terms of ground covered annually, selecting trees to fell, and preserving the remaining trees, but it resulted in an ecologically healthy, mixed-age forest. Biltmore’s hybrid method harvested 1/5 of the property over five years, creating a 25-year harvest cycle, in a high-forest rotation. But as in a selective harvest, only trees over 130 years of age were harvested, all others left to continue growing [12]. Pinchot published the physical and economic results of the first years’ work in a pamphlet distributed at the Chicago Columbian Exposition, a report that Garden and Forest called “a most important step in the progress of American civilization” [13].

Pinchot proved that the forest could be simultaneously materially, economically, and ecologically productive. In addition, Olmsted and Pinchot envisioned several other innovations: an arboretum, a nursery, and the nation’s first, albeit short-lived, school of forestry at Biltmore, which was implemented by Pinchot’s successor at Biltmore, Carl Schenck. The arboretum was to display both ornamental and forestry trees, while the nursery provided trees and shrubs not only to Biltmore itself, but to landscape projects around the country. (In a planting plan where the entry road alone contained over 5,000 rhododendrons, an on-site nursery made a great deal of sense.) The nine-mile-long linear arboretum was to be planted along one of the roads, with trees “classified and arranged for study,” to be “an Experiment Station and Museum of living trees” [14]. While the arboretum never reached Olmsted’s vision, the 300-acre nursery was one of the top nurseries in the country, and in fact the world, for twenty years [15].

A pine plantation along one of the hillsides will grow in to create a frame for the new carriage road. (Image courtesy of the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site)

The National Conservation Conversation

Although a private estate, Biltmore reflected Olmsted’s conservation ethic, a polemic that spanned his career from his early work on Central Park, through his campaigning for a national park system, and in his park designs for natural monuments such as Yellowstone and Niagara Falls. In the same 1876 letter to the Central Park Commission president that had outlined a Central Park forest laboratory, Olmsted had written that “the conservation of Woods and Forests…will soon be [a subject] of great national concern….Our sources of supply for all productions of the forest are rapidly shrinking, while the demand for them on the whole is prodigiously increasing” [16]. He went on to describe the benefits of forestry on deforested lands, and to explain the difficulty of scientific observation of forestry, due to the long time span of trees.

Olmsted believed that extraordinary lands should be preserved as public lands in support of a Jeffersonian ideal of a physically and politically healthy citizenry. State and national parks, Olmsted felt, should be reserves against the “false taste, the caprice or the requirements of some industrial speculation of their holders” that could result from the privatization of lands in the westward expansion [17].

Like Olmsted, Pinchot saw the management and use of the nation’s landscapes and natural resources as an issue of social justice. “The conservation issue is a moral issue, and the heart of it is this: For whose benefit shall our natural resources be conserved – for the benefit of us all, or for the use and profit of the few,” he asked young, politically ambitious men in 1910, before encouraging them to enter politics as a way to effect a more socially just natural resource policy [18]. Pinchot’s utilitarian philosophy, in which he sought “the greatest good of the greatest number in the long-run,” addressed the social ills resulting from industrialization. His was a modern forestry: scientific, functional, efficient.

Where most Americans saw a conflict between forest conservation and timber extraction, Olmsted and Pinchot saw the two as coexisting — healthy forests could produce useful timber. Like Olmsted’s scientific farming, Pinchot’s forestry was based in an understanding of edaphic and biotic ecological systems, and sought to optimize production of a crop or service through interventions into the processes of these systems.

To manage or to protect? This disagreement between preservation and conservation spanned Pinchot’s life and continues today. While on the National Forest Commission, Pinchot clashed with botanist Dr. Charles S. Sargent, director of the Arnold Arboretum, and founder of the influential weekly publication Garden and Forest [19]. Sargent believed that the national forests should be preserved as wilderness; Pinchot believed they should be managed productively for multiple services and functions. Pinchot’s diary entry on the dispute reads, “Sargent opposed to all real forest work, and utterly without a plan or capacity to decide on plans submitted. Meeting a distinct fizzle” [20]. This dispute continued in the famous disagreements between Pinchot and John Muir, and indeed continues today in discussions of the desired future condition of a forest and what cultural uses we want or need therein.

Olmsted’s firm agreed with Pinchot. Olmsted’s partner, Charles Eliot, wrote in Garden and Forest in 1897 about the need to manage forests, not simply protect and preserve them. Speaking against the “all too prevalent feeling that nothing can justify the felling of a tree,” Eliot wrote, “unless this superstition can be put to rout, we may as well attempt no parks or reservations, for if the axe cannot be kept going, Nature will soon reduce the scenery of such domains to a monotony of closely crowded, spindling tree trunks” [21]. Clearly, the Olmsted firm believed, as Pinchot did, that for forests to provide a social and cultural benefit, they must be managed, not merely protected.

Along with timber and nursery stock, the forests at Biltmore produced knowledge. Here, Biltmore Forest School students establish a plantation along Coxe Ridge [Left], and measure logs and estimate yields [Right]. (Images courtesy National Forests of North Carolina Historic Photographs, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville)

“How Shall the Use of the Axe be Guided?”

The Olmsted firm instilled their work, and that of the larger profession of landscape architecture, with the new understanding of forestry processes tested at Biltmore. Olmsted had told his son, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. (Rick), that “Your school for nearly all wisdom in trees and plants and planting is at Biltmore” [22]. When, in 1895, Rick became a partner in the Olmsted firm, he brought to the firm extensive knowledge from his education at Biltmore: horticultural and nursery knowledge, forest composition and management, and the financial aspects of the nursery trade and forestry. As the most influential landscape architecture practice in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century, the Olmsted firm’s approach to forestry filtered out to the larger profession of landscape architecture even as it influenced their own design of urban park systems, university campuses, and civic monuments.

Yet even as scientific forestry infused the Olmsted practice, the two professions began to distance themselves and stake out their disciplinary turf. A debate played out in the pages of Garden and Forest. In 1897, Charles Eliot asked the question, “how shall the use of the axe be guided?” An earlier editorial had proposed that public parks require expert knowledge and maintenance of trees and forest, often through thinning, and that Americans “object on general principles and on all occasions to cutting down a tree;” forests in parks throughout America were severely neglected and their trees in very poor heath as a result [23]. Eliot conceded that foresters — “experts,” — must be “engaged at least as teachers of technical methods,” but argued that the work of foresters needed to done within the framework of a designer’s long-term vision, staking public parks as the domain of the designer. “But how shall the experts themselves be guided?” Elliot asked. “Shall they be permitted to reduce the groves and woods of our public domains to collections of specimen trees, or to the monotony of the typical German forests, as, by the way, they surely will do if they are not controlled?…Engineers who direct the building of park roads are expected to conform their work to the requirements of the adopted general plan. Woodmen, foresters and planters should be similarly controlled by the requirements of the same plan” [24].

Similarly, and in the same venue, Pinchot sought to define his field as a distinct profession. In 1895, he wrote polemically:

“Forestry deals exclusively with forests — a fact which will bear a good deal more publicity than has been accorded to it hitherto. It is connected with arboriculture and landscape art only from the fact that it employs to a certain extent the same raw material, if I may use such a figure, but applies it to a wholly different purpose. That the subjects overlap at certain points is therefore true, but so do carpentry and the manufacture of wood-pulp paper, yet there is no confusion between them. That wise forest-management secures the natural beauty of a region devoted to it is a fortunate accident, but none the less an accident, pure and simple. The purpose of forestry is in a totally different sphere” [25].

With the dawn of the twentieth century and the first mature stirrings of modernism, professions began to differentiate themselves and to lose the “disposition to ready and cordial cooperation between these branch professions … desirable for the public interests” that Olmsted Sr. had called for a decade earlier [26].

The ramble, walled garden, and esplanade and water garden represent three natures: wild, productive, and perfected. They are a treatise on the nature of nature, carved out of the woods. To create the sense of a clearing in the woods, the forests around the house and gardens had to be re-established through plantations. (Images courtesy of the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site, collaged by author)

“Ready and cordial cooperation”

For a few brief years, at the end of Olmsted’s career and the beginning of Pinchot’s, landscape architects and foresters spoke the same language, worked the same problems. Olmsted was, in Pinchot’s words, “one of the men of the century,” [27] a great pre-professional, synthetic designer who knew no professional boundaries and whose projects hybridized aesthetics, infrastructure, ecology, social justice, and economic productivity. Pinchot, one of the giants of his generation, carving out a new profession in America, was an early champion of the modernist value of elegant efficiency. Biltmore occupies a key temporal moment, situated at the emergence of a mature modernism.

Olmsted’s Romantic ethic and aesthetic informed his definition of and attitude towards nature. And his generation valued broad, synthetic knowledge. Farmer, journalist, landscape architect, sanitation secretary — Olmsted practiced across a range of fields. Yet he regretted his lack of deep, scientific training. He appreciated his son’s work for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey as a way to learn “topographical common sense,” and urged his study at Biltmore as a way to “establish the names of plants in your memory and attach ideas, figures, pictures to these names….No one here [at the Olmsted firm’s Brookline office] has done half enough of this” [28].

Pinchot, meanwhile, fully embraced this optimistic, modernist faith in scientific knowledge, and advocated for specialized training and professionalization. Olmsted and Pinchot were both seminal figures in the professionalization of their fields, and by the end of Pinchot’s career, one’s practice was rapidly becoming one’s profession, with associated training, and increasingly, examination and licensure. This undoubtedly led to more rigorous, deep practice, in all environmental design and stewardship fields. But it also distanced fields from one another, and Pinchot’s modernist, utilitarian praxis has led to forests “like well-managed orchards” [29]. Biltmore suggests ways to recover some of the deep roots of “ready and cordial cooperation,” and perhaps suggests the urban forest — complex, enmeshed in social and cultural processes, and long neglected by foresters and conservationists alike — as the site for deeper cross-disciplinary engagement and collaboration.

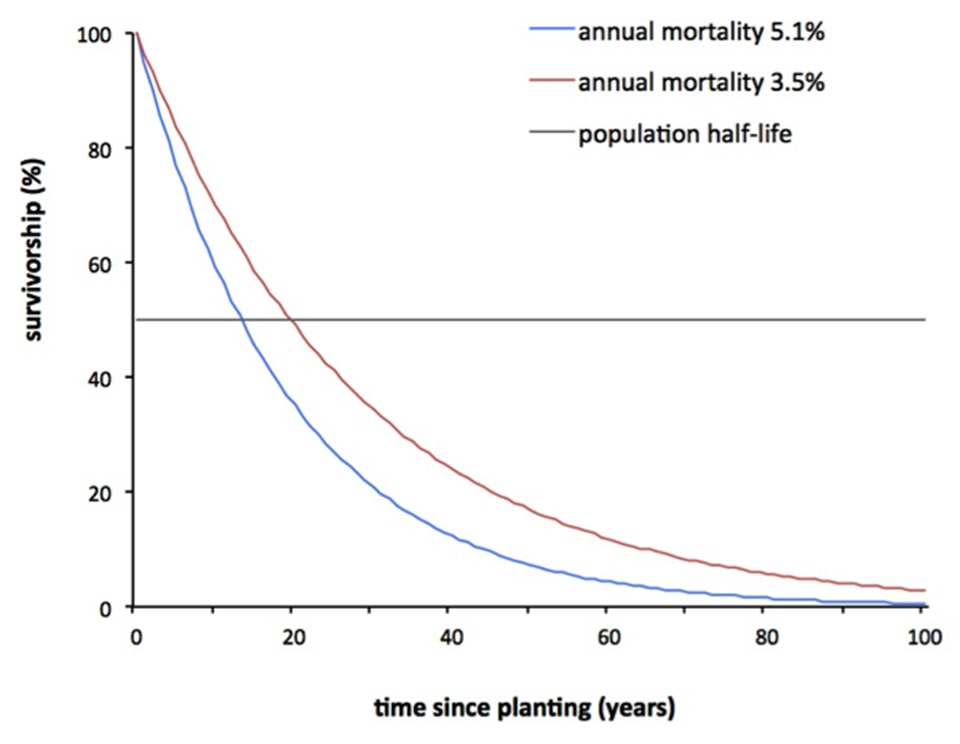

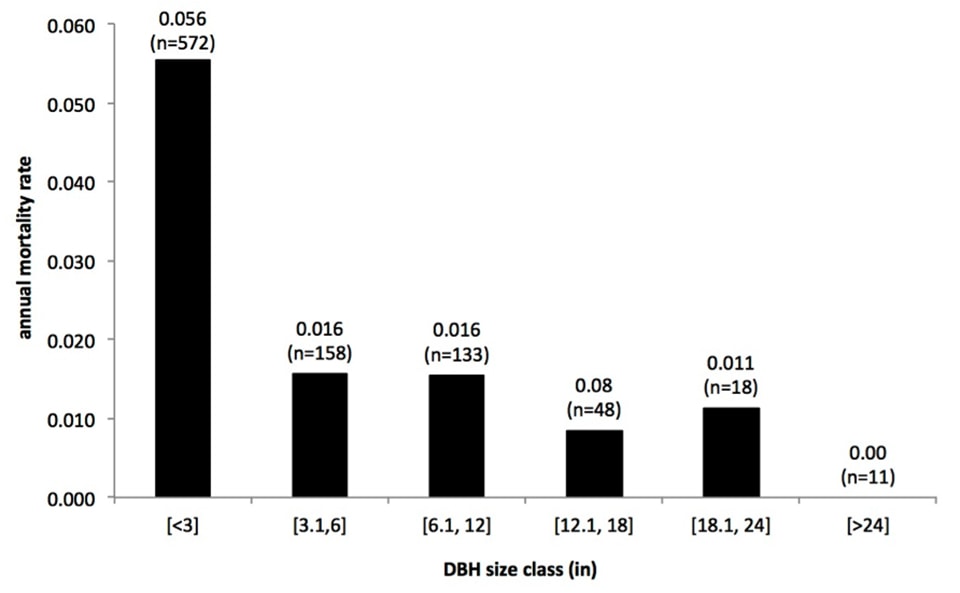

One of the lessons of Biltmore concerns time. Forests — as crops, as a collection of species, as habitats and systems — have time frames well beyond that of a human life. At H.J. Andrews Experimental Research Forest, in Oregon, researchers are nearing the fourth decade of a 200-year-long log decomposition experiment. Because of the duration of forest systems, we still do not understand, fully, scientifically, something so seemingly simple as decomposition. How can we act in a system whose fundamental processes we do not understand?

At Biltmore, the Olmsted firm designed for at least a century, and designed with what ecologist John Magnuson calls “the invisible present” of growth, succession, and decay, as well as the invisible present of modernity and professionalization [30]. Pinchot managed the Biltmore forests for timber yields, which may not be our primary desire for most urban forests. But his choreography of the forest across space and time, accounting for trees, water, animals, and people as actors, provides lessons for today’s designer. The invisible present includes agents of change: climate change and invasive plants and insects that stress or eliminate some tree species; animal browsing or human maintenance that eliminates entire next generations of seedlings; cultural desires that limit the robustness of the forest.

A second set of lessons from Biltmore relates to collaboration between fields, and design for multiplicity. Olmsted wanted the Biltmore forests to produce nursery stock, pleasure, economic return, improved soil, and education. Pinchot described various ways that a forest could be useful: environmental protection of water and soil; material production of timber, nuts, habitat; monetary production as an investment. Both saw the forest producing professional knowledge and political agency. Olmsted and Pinchot pushed each other to imagine more. To see a forest as only ecological, only aesthetic, only economic limits our capacity for invention, while collaboration between fields expands our sense of possibility.

Before: The woods at Biltmore when Vanderbilt purchased them were generally of poor quality, requiring thinning and replanting [Left].

After: Forestry prescriptions such as “coppice under standards” were used to generate sustainable yields of timber from the property. A mature white pine forest on the estate [Right]. (Images courtesy National Forests of North Carolina Historic Photographs, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville)

After: Forestry prescriptions such as “coppice under standards” were used to generate sustainable yields of timber from the property. A mature white pine forest on the estate [Right]. (Images courtesy National Forests of North Carolina Historic Photographs, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville)

And a third lesson of Biltmore is to recognize what Elizabeth Meyer calls “sites of invention.” Olmsted and Pinchot saw the devastation of extant forests, and they fought to set aside large tracts of land and to establish methods for managing those tracts. The threatened site of extant forests fostered the invention of the conservation movement and national forests. Today we find ourselves in a different context, with new challenges and opportunities. We have already had our national conversation about those large forests, and they have been placed, appropriately, under the long-term care of foresters, not landscape architects. We are still trying to truly understand urban forests, and here is where we need to apply our understanding of both cultural and ecosystem values, of both urban and forest composition, structure and function, of recreation and arboriculture, in a synthetic and interdisciplinary way. The urban forest is a contemporary site of invention, and it is here that professional collaboration may hold the most promise. At Biltmore, the two men dealt with a degraded, eroded, depleted landscape. While rural in setting, it had challenges common to an urban site, and forestry offered them an ameliorative, productive practice. We may find the same to hold in the urban forest.

Both landscape design and forest design are simultaneously hopeful and futile acts. They deny the lie of the master plan, with designs that set processes in motion. They envision a future condition that will likely never be, but set the stage for a new design in the next generation.

Many cities are currently inventorying their urban forests, a critical first step to a forest management plan. Foresters, planners, and designers are repeating in cities what Pinchot did at Biltmore: quantifying the benefits of the forest, and providing a baseline against which to measure improvements or failures. Concurrent with these metrics, we need a national conversation on how and why we value the forest. In Pinchot’s era, the forests in the United States were open for development, and very much under threat. Pinchot and Theodore Roosevelt set aside over 160,000,000 acres of national forests, a staggering public trust of beauty, habitat, and ecosystems services. What is the public trust we will leave for the future?

Roxi Thoren is an associate professor in the departments of architecture and landscape architecture at the University of Oregon. Prior to joining the UO, she practiced architecture and landscape architecture in Boston, Charlottesville, and Philadelphia. She is the author of Landscapes of Change, to be released in fall 2014, in which she examines innovative landscape architectural strategies that respond to new social and physical contexts. Professor Thoren is the Director of the UO’s Fuller Center for Productive Landscapes, which investigates the integration of productivity in landscape architecture design, including most recently a series of projects around forestry.

Roxi Thoren is an associate professor in the departments of architecture and landscape architecture at the University of Oregon. Prior to joining the UO, she practiced architecture and landscape architecture in Boston, Charlottesville, and Philadelphia. She is the author of Landscapes of Change, to be released in fall 2014, in which she examines innovative landscape architectural strategies that respond to new social and physical contexts. Professor Thoren is the Director of the UO’s Fuller Center for Productive Landscapes, which investigates the integration of productivity in landscape architecture design, including most recently a series of projects around forestry.

Notes

[1] Gifford Pinchot, Breaking New Ground (Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 1972), 32.

[2] Frederick Law Olmsted to Frederick J. Kingsbury, January 20, 1891, Frederick Law Olmsted Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

[3] Bill Alexander, “Biltmore Estate’s Forestry Legacy,” Forest Landowner, January / February, 2011.

[4] Frederick Law Olmsted to Henry G. Stebbins, February 1, 1876, in The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, Vol. VII: Parks, Politics, and Patronage, 1874-1882, ed. Charles E. Beveridge et al. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007), 175-6.

[5] “A Modern Massachusetts Farm,” Garden and Forest, March 30, 1892, 145-6.

[6] “Project of Operations for Improving the Forest of Biltmore,” no date, Biltmore Estate Archives, Asheville, NC.

[7] Frederick Law Olmsted and J. B. Harrison, “Observations on the Treatment of Public Plantations, More Especially Related to the Use of the Axe,” in Forty Years of Landscape Architecture: Central Park, eds. Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and Theodora Kimball, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1973), 362-75.

[8] For Pinchot’s essays on the Sihlwald, see Garden and Forest vol 3, issues 127-129; for European forest policy, see vol. 4, issues 150-152.

[9] Nancy P. Pittman, in “James Wallace Pinchot (1831-1908): One Man’s Evolution toward Conservation in the Nineteenth Century” (Yale F&ES Centennial News. Fall 1999, 5) describes James Pinchot and Olmsted’s membership in the exclusive Century Association. Olmsted and James Pinchot’s friendship is described in the USDA’s Historic Structures Report: Grey Towers (United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. FS-327, 2) and in Laura Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973), 418-19.

[10] Gifford Pinchot, journal entry August 11, 1937, in The Conservation Diaries of Gifford Pinchot, ed. Harold K. Steen (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2001), 174.

[11] Dan Handel, “Into the Woods,” Cabinet, 48 (2012/13).

[12] Standard forestry practices are from US Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Forestry, A Primer of Forestry. Part II: Practical Forestry, by Gifford Pinchot, Bulletin 24, part 2, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1905). Biltmore forestry practices are from Gifford Pinchot, Biltmore Forest: An Account of its Treatment, and the Results of the First Year’s Work, Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1893.

[13] “Mr. Vanderbilt’s Forest,” Garden and Forest, February 21, 1894, 71.

[14] Frederick Law Olmsted, “George W. Vanderbilt’s Nursery,” Garden and Forest, December 30, 1891, 615.

[15] Charles E. Beveridge, “’The First Great Private Work of Our Profession in the Country’ Frederick Law Olmsted, Senior, at Biltmore,” National Association for Olmsted Parks Workbook, 5, no. 3 (1995), and Bill Alexander, The Biltmore Nursery: A Botanical Legacy, (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2007), 11.

[16] Frederick Law Olmsted to Henry G. Stebbins, 1 February 1876, in The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, Vol. VII: Parks, Politics, and Patronage, 1874-1882, ed. Charles E. Beveridge et al. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007), 175-6.

[17] Frederick Law Olmsted, “Preliminary Report upon the Yosemite and Big Tree Grove” in The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, Vol. V: The California Frontier, 1863-1865, ed. Victoria Post Ranney et al. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990), 488-518

[18] Gifford Pinchot, address to the Roosevelt Club of St. Paul, Minnesota, June 11, 1910.

[19] M. Nelson McGeary, Gifford Pinchot: Forester – Politician (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1960), 39.

[20] Gifford Pinchot, journal entry May 16, 1896, in The Conservation Diaries of Gifford Pinchot, ed. Harold K. Steen (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2001), 72.

[21] Charles Eliot, “Trees in Public Parks,” Garden and Forest, January 27, 1897, 37.

[22] Susan L. Klaus, “’A Better School Could Scarcely be Found’ Frederick Law Olmsted, Junior, at Biltmore,” in The Olmsteds at Biltmore: Frederick Law Olmsted, Senior, eds. Charles E. Beveridge and Susan L. Klaus, (Bethesda, Md: National Association for Olmsted Parks, 1995).

[23] “Trees in Public Parks,” Garden and Forest, Dec. 23, 1896, 511.

[24] Charles Eliot, “Trees in Public Parks,” Garden and Forest, January 27, 1897, 37.

[25] Gifford Pinchot, “The Need of Forest Schools in America,” Garden and Forest, July 24, 1895, 298.

[26] Frederick Law Olmsted, “Paper on the Back Bay Problem and Its Solution,” in The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted: Supplementary Series Vol. 1 Writings on Public Parks, Parkways, and Park Systems, eds. Charles E. Beveridge and Carolyn F. Hoffman (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 437-460.

[27] Pinchot, Breaking New Ground, 48.

[28] Charles E. Beveridge, “’The First Great Private Work of Our Profession in the Country’ Frederick Law Olmsted, Senior, at Biltmore,” National Association for Olmsted Parks Workbook, 5, no. 3 (1995)

[29] Alan G. McQuillan, “Cabbages and Kings: The Ethics and Aesthetics of New Forestry,” Environmental Values 2 (1993): 205.

[30] John J. Magnuson, “Long-Term Ecological Research and the Invisible Present,“ BioScience, 40, no. 7, (1990): 495.

For further information log on website :https://scenariojournal.com/article/deep-roots/