Woodworking is the activity or skill of making items from wood and includes cabinet making (Cabinetry and Furniture) wood carving, joinery and carpentry.

History

Woodworking was essential to the Romans. It provided, sometimes the only, material for buildings, transportation, tools, and household items. Wood also provided pipes, dye, waterproofing materials, and energy for heat.1Although most examples of Roman woodworking have been lost,:2 the literary record preserved much of the contemporary knowledge. Vitruvius dedicates an entire chapter of his De architectura to timber, preserving many details. Pliny, while not a botanist, dedicated six books of his Natural History to trees and woody plants which provides a wealth of information on trees and their uses

Ancient China

The progenitors of Chinese woodworking are considered to be Lu Ban (魯班) and his wife Lady Yun, from the Spring and Autumn Period. Lu Ban is said to have introduced the plane, chalk-line, and other tools to China. His teachings were supposedly left behind in the book Lu Ban Jing (魯班經, "Manuscript of Lu Ban"). Despite this, it is believed that the text was written some 1500 years after his death. This book is filled largely with descriptions of dimensions for use in building various items such as flower pots, tables, altar etc., and also contains extensive instructions concerning Feng Shui.It mentions almost nothing of the intricate glue-less and nail-less joiner for which Chinese furniture was so famous.

With the advances in modern technology and the demands of industry, woodwork as a field has changed. The development of Computer Numeric Controlled (CNC) Machines, for example, has made us able to mass-produce and reproduce products, faster, with less waste, and often more complex in design than ever before. Skilled fine woodworking, however, remains a craft pursued by many. There remains demand for hand crafted work such as furniture and arts, however with rate and cost of production, the cost for consumers is much higher.

Materials

References

External Links

Video about the Zafimaniry peoples in Madagascar.

- Wikipedia

History

Along with stone, clay and animal parts, wood was one of the first materials worked by early humans. Microwear analysis of the Mousterian stone tools used by the Neanderthals show that many were used to work wood. The development of civilization was closely tied to the development of increasingly greater degrees of skill in working these materials.

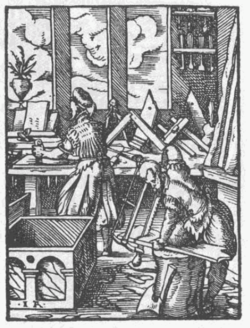

Woodworking shop in Germany in 1568, the worker in front is using a bow saw, the one in the background is planing.

Among early finds of wooden tools are the worked sticks from Kalambo Falls, Clacton-on-Sea and Lehringen. The spears from Schöningen (Germany) provide some of the first examples of wooden hunting gear. Flint tools were used for carving. Since Neolithic times, carved wooden vessels are known, for example, from the Linear Pottery culture wells at Kückhofen and Eythra.

Examples of Bronze Age wood-carving include tree trunks worked into coffins from northern Germany and Denmark and wooden folding-chairs. The site of Fellbach-Schmieden in Germany has provided fine examples of wooden animal statues from the Iron Age Wooden idols from the La Tène period are known from a sanctuary at the source of the Seine in France.

Ancient Egypt

There is significant evidence of advanced woodworking in Ancient Egypt. Woodworking is depicted in many extant ancient Egyptian drawings, and a considerable amount of ancient Egyptian furniture (such as stools, chairs, tables, beds, chests) has been preserved. Tombs represent a large collection of these artefacts and the inner coffins found in the tombs were also made of wood. The metal used by the Egyptians for woodworking tools was originally copper and eventually, after 2000 BC bronze as ironworking was unknown until much later.

Commonly used woodworking tools included axes, adzes chisels pull saws and bow drills. Mortise and teno joints are attested from the earliest Predynastic period. These joints were strengthened using pegs, dowels and leather or cord lashings. Animal glue came to be used only in the New Kingdom period Ancient Egyptians invented the art of veneering and used varnishes for finishing, though the composition of these varnishes is unknown. Although different native acacias were used, as was the wood from the local sycamore and tamarisk trees, deforestation in the Nile valley resulted in the need for the importation of wood, notably cedar, but also Aleppo pine, boxwood and oak, starting from the Second Dynasty.

Ancient RomeWoodworking was essential to the Romans. It provided, sometimes the only, material for buildings, transportation, tools, and household items. Wood also provided pipes, dye, waterproofing materials, and energy for heat.1Although most examples of Roman woodworking have been lost,:2 the literary record preserved much of the contemporary knowledge. Vitruvius dedicates an entire chapter of his De architectura to timber, preserving many details. Pliny, while not a botanist, dedicated six books of his Natural History to trees and woody plants which provides a wealth of information on trees and their uses

Ancient China

The progenitors of Chinese woodworking are considered to be Lu Ban (魯班) and his wife Lady Yun, from the Spring and Autumn Period. Lu Ban is said to have introduced the plane, chalk-line, and other tools to China. His teachings were supposedly left behind in the book Lu Ban Jing (魯班經, "Manuscript of Lu Ban"). Despite this, it is believed that the text was written some 1500 years after his death. This book is filled largely with descriptions of dimensions for use in building various items such as flower pots, tables, altar etc., and also contains extensive instructions concerning Feng Shui.It mentions almost nothing of the intricate glue-less and nail-less joiner for which Chinese furniture was so famous.

Damascene woodworkers turning, wood for mashrabia and hookass, 19th century.

Micronesian of Tobi, Palau, making a paddle for his wa with an adze.

Modern DayWith the advances in modern technology and the demands of industry, woodwork as a field has changed. The development of Computer Numeric Controlled (CNC) Machines, for example, has made us able to mass-produce and reproduce products, faster, with less waste, and often more complex in design than ever before. Skilled fine woodworking, however, remains a craft pursued by many. There remains demand for hand crafted work such as furniture and arts, however with rate and cost of production, the cost for consumers is much higher.

Materials

Historically, woodworkers relied upon the woods native to their region, until transportation and trade innovations made more exotic woods available to the craftsman. Woods are typically sorted into three basic types: hardwoods typified by tight grain and derived from broadleaf trees, softwoods from coniferous trees, and man-made materials such as plywood and MDF.

Typically furniture such as tables and chairs is made using solid stock, and cabinet/fixture makers employ the use of plywood and other man made panel products

Notes- ^ Killen, Geoffrey (1994). Egyptian Woodworking and Furniture. Shire Publications. ISBN 0747802394.

- ^ Leospo, Enrichetta (2001), "Woodworking in Ancient Egypt", The Art of Woodworking, Turin: Museo Egizio, p.20

- ^ Leospo, pp.20-21

- ^ Leospo, pp. 17-19

- ^ a b Ulrich, Roger B. (2008). Roman Woodworking. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300134605 OCLC 192003268.

- ^ Vitruvius. De architectura. 1:2.9.1.

- ^ Pliny. Natural History.

- Feirer, John L. (1988). Cabinetmaking and Millwork. Mission Hills California: Glencoe Publishing. ISBN 0-02-675950-0.

- Frid, Tage (1979). Tage Frid Teaches Woodworking. Newton, Connecticut: Taunton Press. ISBN 0-918804-03-5.

- Joyce, Edward; revised and expanded by Alan Peters (1987). Encyclopedia of Furniture Making. New York: Sterling Publishing Co. ISBN 0-8069-6440-5. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - Roubo, André Jacob (1769–1784). The Art of the Joiner. Paris: French Academy of Sciences.

Further reading

- Naylor, Andrew. A review of wood machining literature with a special focus on sawing. BioRes, April 2013

Video about the Zafimaniry peoples in Madagascar.

- Wikipedia