" This article is about cattle used for draft. For other uses of "ox" or "oxen", see Ox (disambiguation). For other uses of "bullock", see Bullock (disambiguation)".

Not to be confused with aurochs or musk ox.

An ox (plural oxen), also known as a bullock in Australia and India, is a bovine trained as a draft animal. Oxen are commonly castrated, adult male cattle; castration makes the animals easier to control. Cows (adult females) or bulls (intact males) may also be used in some areas.

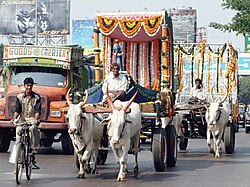

Zebu oxen in Mumbai, India.

Oxen are used for plowing, for transport pulling carts, hauling wagons and even riding), for threshing, grain by trampling, and for powering machines that grind grain or supply irrigation among other purposes. Oxen may be also used to skid logs in forests, particularly in low-impact, select-cut logging.

Oxen are usually yoked in pairs. Light work such as carting household items on good roads might require just one pair, while for heavier work, further pairs would be added as necessary. A team used for a heavy load over difficult ground might exceed nine or ten pairs.

Oxen used in farms for plowing

DomesticationOxen are thought to have first been harnessed and put to work around 4000 BC.

Training

Working oxen are taught to respond to the signals of the teamster, bullocky or ox-driver. These signals are given by verbal command and body language, reinforced by a goad, whip or a long pole (which also serves as a measure of length: see rod). In pre-industrial times, most teamsters were known for their loud voices and forthright language.

A team of ten pairs of oxen in Australia.

Verbal commands for draft animals vary widely throughout the world. In North America, the most common commands are:

- Back: back up

- Gee: turn to the right

- Get up (also giddyup or giddyap, contractions for "get thee up" or "get ye up"): go

- Haw: turn to the left

- Whoa: stop

In the New England tradition, young castrated cattle selected for draft are known as working steers and are painstakingly trained from a young age. Their teamster makes or buys as many as a dozen yokes of different sizes for each animal as it grows. The steers are normally considered fully trained at the age of four and only then become known as oxen.

A tradition in south eastern England was to use oxen (often Sussex cattle) as dual-purpose animals: for draft and beef. A plowing team of eight oxen normally consisted of four pairs aged a year apart. Each year, a pair of steers of about three years of age would be bought for the team and trained with the older animals. The pair would be kept for about four years, then sold at about seven years old to be fattened for beef – thus covering much of the cost of buying that year's new pair. Use of oxen for plowing survived in some areas of England (such as the South Downs) until the early twentieth century. Pairs of oxen were always hitched the same way round, and they were often given paired names. In southern England it was traditional to call the near-side (left) ox of a pair by a single-syllable name and the off-side (right) one by a longer one (for example: Lark and Linnet, Turk and Tiger).

Ox trainers favour larger animals for their ability to do more work. Oxen are therefore usually of larger breeds, and are usually males because they are generally larger. Females can also be trained as oxen, but as well as being smaller, they are often more valued for producing calves and milk. Bulls are also used in many parts of the world, especially Asia and Africa.

Shoeing

Karel Dujardin, 1622–1678: A Smith Shoeing an Ox

Working oxen usually require shoes, although in England not all working oxen were shod. Since their hooves are cloven, two shoes or ox cues are required for each hoof, unlike the single shoe of a horse. Ox shoes are usually of approximately half-moon or banana shape, either with or without caulkins and are fitted in symmetrical pairs to the hooves. Unlike horses, oxen are not easily able to balance on three legs while a farrier shoes the fourth. In England, shoeing was accomplished by throwing the ox to the ground and lashing all four feet to a heavy wooden tripod until the shoeing was complete. A similar technique was used in Serbia and, in a simpler form, in India, where it is still practiced In Italy, where oxen may be very large, shoeing is accomplished using a massive framework of beams in which the animal can be partly or completely lifted from the ground by slings passed under the body; the feet are then lashed to lateral beams or held with a rope while the shoes are fitted.

A single left-hand ox shoe of the type used for large Chianina oxen in Tuscany.

Such devices were made of wood in the past, but may today be of metal. Similar devices are found in France, Austria, Germany, Spain, Canada and the United States, where they may be called ox slings, ox presses or shoeing stalls. The system was sometimes adopted in England also, where the device was called a crush or trevis; one example is recorded in the Vale of Pewsey. The shoeing of an ox partly lifted in a sling is the subject of John Singer Sargent's painting Shoeing the Ox, while A Smith Shoeing an Ox by Karel Dujardin shows an ox being shod standing, tied to a post by the horns and balanced by supporting the raised hoof.

Ox shoeing sling in the Dorfmuseum of Mönchhof, Austria; a pair of ox shoes is attached to the near left column

Uses and Comparison to Other Draught Animals

Oxen can pull heavier loads, and pull for a longer period of time than horses depending on weather conditions. On the other hand, they are also slower than horses, which has both advantages and disadvantages; their pulling style is steadier, but they cannot cover as much ground in a given period of time. For agricultural purposes, oxen are more suitable for heavy tasks such as breaking sod or ploughing in wet, heavy, or clay-filled soil. When hauling freight, oxen can move very heavy loads in a slow and steady fashion. They are at a disadvantage compared to horses when it is necessary to pull a plow or load of freight relatively quickly.

Riding an ox in Hova, Sweden.

For millennia, oxen also could pull heavier loads because of the use of the yoke, which was designed to work best with the neck and shoulder anatomy of cattle. Until the invention of the horse collar, which allowed the horse to engage the pushing power of its hindquarters in moving a load, horses could not pull with their full strength because the yoke was incompatible with their anatomy.

Well-trained oxen are also considered less excitable than horses.

References- ^ "HISTORY OF THE DOMESTICATION OF ANIMALS. Historyworld.net. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Conroy, Drew (2007). Oxen, A Teamster's Guide. North Adams, Massachusetts, USA: Storey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58017-693-4.

- ^ Copper, Bob, A Song for Every Season: A Hundred Years of a Sussex Farming Family(pp 95–100), Heinemann 1971

- ^ John C Barret (1991), "The Economic Role of Cattle in Communal Farming Systems in Zimbabwe", to be published in Zimbabwe Veterinary Journal, p 10.

- ^ Draught Animal Power, an Overview, Agricultural Engineering Branch, Agricultural Support Systems Division, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

- ^ a b c Williams, Michael (17 September 2004). "The Living Tractor. Farmers Weekly. Retrieved May 2011.

- ^ a b Watts, Martin (1999). Working oxen. Princes Risborough: Shire. ISBN 0-7478-0415-X.

- ^ a b Baker, Andrew (1989). "Well Trained to the Yoke: Working Oxen on the Village's Historical Farms". Old Sturbridge Village. Retrieved May 2011.

- ^ Schomberg, A. (7 November 1885). "Shoeing oxen and horses at a Servian smithy. The Illustrated London News. Retrieved May 2011.

- ^ "Blacksmith shoeing a Bullock, Calcutta, India", stereoscope card (half only)). Stereo-Travel Co. 1908. Retrieved May 2011.

- ^ Aliaaaaa (2006). "Restraining and Shoeing", Bangalore, Karnataka, India. Retrieved May 2011.

- ^ Tacchini, Alvaro. "La ferratura dei buoi (in Italian). Retrieved May 2013.

The shoeing of the oxen

- ^ "Tradizioni - Serramanna (in Italian and Sardinian). Retrieved May 2011.

Serramanna: traditions.

- ^ Wet Dry Routes Chapter Newlsletter 4 (4). 1997 http://www.santafetrailresearch.com/wet/vol-06-no-4.html. Retrieved May 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help). - ^ Wet Dry Routes Chapter Newlsletter 6 (4). 1999 http://www.santafetrailresearch.com/wet/vol-06-no-4.html. Retrieved May 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help). - ^ John Singer Sargent. "Shoeing the Ox. Retrieved May 2011.

- ^ Taylor, Tess (May 3, 2011). "On Small Farms, Hoof Power Returns. The New York Times. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Conroy, Drew. "Dr." (PDF). Ox Yokes: Culture, Comfort and Animal Welfare. World Association for Transport Animal Welfare and Studies (TAWS). Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- Don't Knock the Ox, Canadian short showing ox-shoeing and ox-pulling

- Rural Heritage-Ox Paddock

- Two articles about oxen compared with horses

- Wikipedia