Agarwood, also known as oud, oodh or agar, is a dark resinous heartwood that forms in Aquilaria and Gyrinops trees (large evergreens native to southeast Asia) when they become infected with a type of mould. Prior to infection, the heartwood is odourless, relatively light and pale coloured; however, as the infection progresses, the tree produces a dark aromatic resin in response to the attack, which results in a very dense, dark, resin embedded heartwood. The resin embedded wood is commonly called gaharu, jinko, aloeswood, agarwood, or oud (not to be confused with bukhoor) and is valued in many cultures for its distinctive fragrance, and thus is used for incense and perfumes.

There are seventeen species in the genus Aquilaria and eight are known to produce agarwood. In theory agarwood can be produced from all members; however, until recently it was primarily produced from A. malaccensis. A. agallocha and A. secundaria are synonyms for A. malaccensis. A. crassna and A. sinensis are the other two members of the genus that are usually harvested.

Formation of agarwood occurs in the trunk and roots of trees that have been infected by a parasitic ascomycetous mould, Phaeoacremonium parasitica, a dematiaceous (dark-walled) fungus. As a response, the tree produces a resin high in volatile organic compounds that aids in suppressing or retarding the fungal growth, a process called tylosis. While the unaffected wood of the tree is relatively light in colour, the resin dramatically increases the mass and density of the affected wood, changing its colour from a pale beige to dark brown or black. In natural forest only about 7% of the trees are infected by the fungus. A common method in artificial forestry is to inoculate all the trees with the fungus. Oud oil can be distilled from agarwood using steam, the total yield of agarwood (Oud) oil for 70 kg of wood will not exceed 20 ml (Harris, 1995).

Aquilaria species that produce agarwood

First grade agarwood

One of the main reasons for the relative rarity and high cost of agarwood is the depletion of the wild resource. Since 1995 Aquilaria malaccensis, the primary source, has been listed in Appendix II (potentially threatened species) by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. In 2004 all Aquilariaspecies were listed in Appendix II; however, a number of countries have outstanding reservations regarding that listing.

Uninfected Aquilaria wood lacking the dark resin.

First-grade agarwood is one of the most expensive natural raw materials in the world. A whole range of qualities and products are on the market, varying in quality with geographical location, botanical species, the age of the specific tree, cultural deposition and the section of the tree where the piece of agarwood stems from. Oud oil is distilled from agarwood, and fetches high prices depending on the oil's purity. The current global market for agarwood is estimated to be in the range of US$6 – 8 billion and is growing rapidly.

History

The odour of agarwood is complex and pleasing, with few or no similar natural analogues. In the perfume state, the scent is mainly distinguished by a combination of "oriental-woody" and "very soft fruity-floral" notes. The incense smoke is also characterized by a "sweet-balsamic" note and "shades of vanilla and musk" and ambergris. As a result, agarwood and its essential oil gained great cultural and religious significance in ancient civilizations around the world, being mentioned throughout one of the world's oldest written texts – the Sanskrit Vedas from India.

As early as the third century AD in ancient China, the chronicle Nan zhou yi wu zhi (Strange things from the South) written by Wa Zhen of the Eastern Wu Dynasty mentioned agarwood produced in the Rinan commandery, now Central Vietnam, and how people collected it in the mountains.

During the sixth century AD in Japan, in the recordings of the Nihon Shoki (The Chronicles of Japan) the second oldest book of classical Japanese history, mention is made of a large piece of fragrant wood identified as agarwood. The source for this piece of wood is claimed to be from Pursat, Cambodia (based on the smell of the wood). The famous piece of wood still remains in Japan today and is showcased less than 10 times per century at the Nara National Museum.

Agarwood’s use as a medicinal product has been recorded in the Sahih Muslim, which dates back to approximately the eighth century, and in the Ayurvedic medicinal text the Susruta Samhita.

Starting in 1580 after Nguyễn Hoàng took control over the central provinces of modern Vietnam, he encouraged trade with other countries, specifically China and Japan. Agarwood was exported in three varieties: Calambac (kỳ nam in Vietnamese), trầm hương (very similar but slightly harder and slightly more abundant), and agarwood proper. A pound of Calambac bought in Hội An for 15 taels could be sold in Nagasaki for 600 taels. The Nguyễn Lords soon established a Royal Monopoly over the sale of Calambac. This monopoly helped fund the Nguyễn state finances during the early years of the Nguyen rule.

Xuanzang's travelogues and the Harshacharita, written in seventh century AD in Northern India, mentions use of agarwood products such as 'Xasipat' (writing-material) and 'aloe-oil' in ancient Assam (Kamarupa). The tradition of making writing materials from its bark still exists in Assam.

Etymology

Aquilaria tree showing darker agarwood. Poachers had scraped off the bark to allow the tree to become infected by the ascomycetous mould.

Agarwood is known under many names in different cultures:

- In Cambodia, it is called "chann crassna". The fragrance from this wood is called "khloem chann" (ខ្លឹមចាន់) or "khloem chann crassna". "khloem" is fragrance, "chann crassna" is the tree species Aquilaria crassna in khmer language.

- In Hindustani, it is known as agar, which is derived originally Sanskrit aguru .

- In Bengali, agarwood is known as "agor/agoro gach(আগর গাছ)" and the agarwood oil as "agor/agoro attor(আগর আতর)".

- It is known by the same Sanskrit name in Telugu,and Kannada,as Aguru.

- It is known as chénxiāng (沉香) in Chinese, "Cham Heong" in Cantonese, trầm hương in Vietnamese, and jinkō (沈香) in Japanese; all meaning "sinking incense" and alluding to its high density. In Japan, there are several grades of jinkō, the highest of which is known as kyara (伽羅).

- Both agarwood and its resin distillate/extracts are known as oud (عود) in Arabic (literally "rod/stick") and used to describe agarwood in Arab countries. Western perfumers also often use agarwood essential oil under the name "oud" or "oudh".

- In Europe it was referred to as Lignum aquila (eagle-wood) or Agilawood, because of the similarity in sound of agila to gaharu.

- Another name is Lignum aloes or Aloeswood. This is potentially confusing, since a genus Aloe exists (unrelated), which has medicinal uses.

- In Tibetan it is known as ཨ་ག་རུ་ (a-ga-ru). There are several varieties used in Tibetan Medicine: unique eaglewood: ཨར་བ་ཞིག་ (ar-ba-zhig); yellow eaglewood: ཨ་ག་རུ་སེར་པོ་ (a-ga-ru ser-po), white eaglewood: ཨར་སྐྱ་ (ar-skya), and black eaglewood: ཨར་ནག་(ar-nag).

- In Assamese it is called as "sasi" or "sashi".

- The Indonesian and Malay name is "gaharu".

- In Hong Kong it is often called Aloeswood

- In Papua New Guinea it is called "ghara" or eaglewood.

- In Thai it is known as "Mai Kritsana" (ไม้กฤษณา).

- In Tamil it is called "akil" (அகில்) though what was referred in ancient Tamil literature could well be Excoecaria agallocha.

- In Laos it is known as "Mai Ketsana" (ໄມ້ເກດສະໜາ).

- In Myanmar (Burma) it is known as "Thit Mhwae".

- In Sri Lanka Agarwood producing Gyrinops walla tree is known as "Walla Patta" (වල්ල පට්ට)

There are seventeen species in the genus Aquilaria and eight are known to produce agarwood. In theory agarwood can be produced from all members; however, until recently it was primarily produced from A. malaccensis. A. agallocha and A. secundaria are synonyms for A. malaccensis. A. crassna and A. sinensis are the other two members of the genus that are usually harvested.

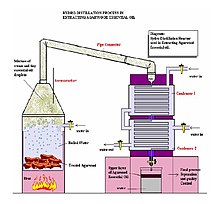

Steam distillation process used to extract agarwood essential oils.

Formation of agarwood occurs in the trunk and roots of trees that have been infected by a parasitic ascomycetous mould, Phaeoacremonium parasitica, a dematiaceous (dark-walled) fungus. As a response, the tree produces a resin high in volatile organic compounds that aids in suppressing or retarding the fungal growth, a process called tylosis. While the unaffected wood of the tree is relatively light in colour, the resin dramatically increases the mass and density of the affected wood, changing its colour from a pale beige to dark brown or black. In natural forest only about 7% of the trees are infected by the fungus. A common method in artificial forestry is to inoculate all the trees with the fungus. Oud oil can be distilled from agarwood using steam, the total yield of agarwood (Oud) oil for 70 kg of wood will not exceed 20 ml (Harris, 1995).

Aquilaria species that produce agarwood

The following species of Aquilaria produce agarwood:

Conservation of agarwood-producing species

Overharvesting and habitat loss threatens some populations of agarwood-producing species. Concern over the impact of the global demand for agarwood has thus led to the inclusion of the main taxa on CITES Appendix II, which requires that international trade in agarwood is monitored by TRAFFIC (a UK-based charity) and is subject to controls designed to ensure that harvest and exports are not to the detriment of the survival of the species in the wild.

In addition, agarwood plantations have been established in a number of countries, and reintroduced into countries such as Malaysia and Sri Lanka as commercial plantation crops. The success of these plantation depends on the stimulation of agarwood production in the trees. Numerous inoculation techniques have been developed, with varying degrees of success.

References- ^ The genus Gyrinops, is closely related to Aquilaria and in the past all species were considered to belong to Aquilaria. Blanchette, Robert A. (2006) "Cultivated Agarwood – Training programs and Research in Papua New Guinea", Forest Pathology and Wood Microbiology Research Laboratory, Department of Plant Pathology, University of Minnesota

- ^ a b Broad, S. (1995) "Agarwood harvesting in Vietnam" TRAFFIC Bulletin 15:96

- ^ a b CITES (25 April 2005) "Notification to the Parties" No. 2005/0025, (PDF) . Retrieved on 2013-07-22.

- ^ a b Dinah Jung, The Value of Agarwood: Reflections upon its use and history in South Yemen, Universitätsbibliothel, Universität Heidelberg, 30 May 2011, (PDF) p. 4.

- ^ International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences, ISSN 2305-0330, Volume 2, Issue 1: January 2013)

- ^ International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences, ISSN 2305-0330, Volume 2, Issue 1: January 2013)

- ^ "Publications: Forestry". Traffic. 2006-11-17. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- ^ Li, Tana (1998) Nguyễn Cochinchina: southern Vietnam in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Southeast Asia Program Publications, Ithaca, New York, p. 79, ISBN 0-87727-722-2.

- ^ Pusey, Edward Bouverie (1885) Daniel the Prophet: Nine Lectures, Delivered in the Divinity School of the University of Oxford Funk & Wagnalls, New York, p. 515, OCLC 5577227.

- ^ "Aguru" in Sanskrit Dictionary from Bhaktivedanta VedaBase Network

- ^ Thứ Hai (9 April 2006) "kỳ nam và trầm hương" Tuổi Trẻ Online. Tuoitre.com.vn. Retrieved on 2013-07-22.

- ^ Morita, Kiyoko (1999). The Book of Incense: Enjoying the Traditional Art of Japanese Scents. Kodansha USA. ISBN 4770023898.

- ^ Burfield, Tony (2005) "Agarwood Trading" The Cropwatch Files, Cropwatch

- ^ Branch, Nathan (30 May 2009) "Dawn Spencer Hurwitz Oude Arabique (extrait)" (fashion and fragrance reviews)

- ^ a b c Yule, Henry and Burnell, Auther Coke (1903) "Eaglewood" Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive (2nd edition) John Murray, London, p. 335, OCLC 33186146.

Snelder, Denyse J.; Lasco, Rodel D. (29 September 2008). Smallholder Tree Growing for Rural Development and Environmental Services: Lessons from Asia. シュプリンガー・ジャパン株式会社. p. 248 ff. ISBN 978-1-4020-8260-3. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

Dr. Jung, Dinah (1 January 2013). The cultural biography of agarwood (PDF). University of Heidelberg: HeiDOK: Journal article: JRAS. p. 103-125. Retrieved January 2016.

External Links- Hong Kong herbarium factsheet of Aquilaria sinensis

- Etymology of agarwood and aloe

- "Sustainable Agarwood Production in Aquilaria Trees" at the University of Minnesota

- Traditional and Medicinal Uses of Aquilaria / Agarwood

- Wikipedia

No comments:

Post a Comment