Author

Karen O. Lutsky is currently an adjunct professor at Pennsylvania State University’s Stuckeman School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Her more recent design research focuses on landscape architecture’s role in the constructed coastlines of the Great Lakes and the potential of the lakes’ re-emergent land to address their larger environmental issues and establish healthier relationships between people and the water. Her work and teaching also incorporates her interests in the accessibility of the design process and design literacy as essential components in the establishment of regional landscape identity and the re-vitalization of large post-industrial sites. She holds a B.A. in Environmental Sociology from Brandeis University and an M.L.A. from the University of Pennsylvania.

For further details log on website :

Karen O. Lutsky is currently an adjunct professor at Pennsylvania State University’s Stuckeman School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Her more recent design research focuses on landscape architecture’s role in the constructed coastlines of the Great Lakes and the potential of the lakes’ re-emergent land to address their larger environmental issues and establish healthier relationships between people and the water. Her work and teaching also incorporates her interests in the accessibility of the design process and design literacy as essential components in the establishment of regional landscape identity and the re-vitalization of large post-industrial sites. She holds a B.A. in Environmental Sociology from Brandeis University and an M.L.A. from the University of Pennsylvania.

For further details log on website :

http://scenariojournal.com/article/big-old-tree-new-big-easy/

Published in Scenario 04: Building the Urban Forest

Spring 2014

Spring 2014

It is a warm day in City Park as I wander through an older grove of live oaks. The trees, with their hulking trunks, twisted branches, and extensive protruding roots, create rooms, ceilings, and seats around me. Their forms speak easily to timeless architectural features. Though massive in size, the trees are incredibly accessible – their features so familiar and human-scaled—as proven by the visitors so often found tucked into a crook of their branches or hanging upside down amid the Spanish moss. These trees are nurturers of place, nostalgic fortresses, and ecological strongholds. Existing well before Katrina or even before the 18th century European settlement, they might be considered the oldest and most sustainable ‘architecture’ in the city. They are big; they are old; and these monuments of fortitude are fundamental to the future landscape of New Orleans.

This project ‘Big Old Tree; New Big Easy’, was a result of an advanced studio in landscape architecture and regional planning at the University of Pennsylvania. At its core, it is an adaptable design proposal built upon the inherent qualities of New Orleans’ native tree species. By exploring a diverse set of values and dynamics, such as the rich historical identity of the trees, their capabilities for environmental and hydrological mitigation, and the social and economic investment that such an urban forestry project demands; this project speaks to the potential of a simple urban forest strategy to engage the past, respond to critical current issues, and maybe most importantly, nurture a ‘sustainable’ future.

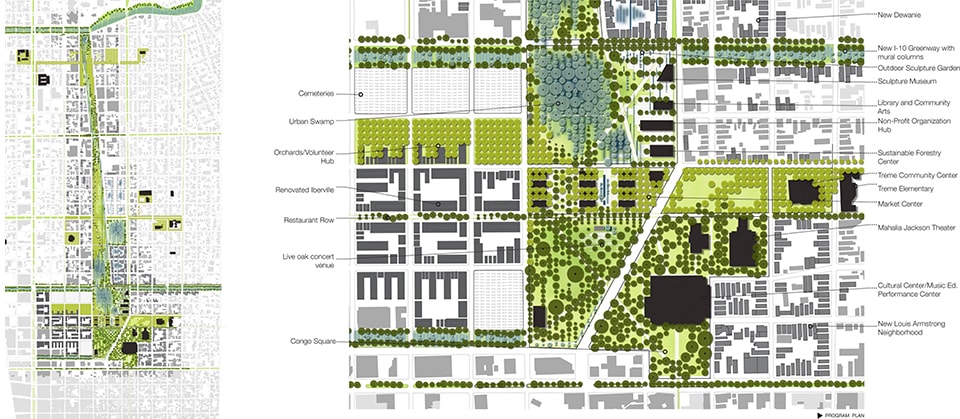

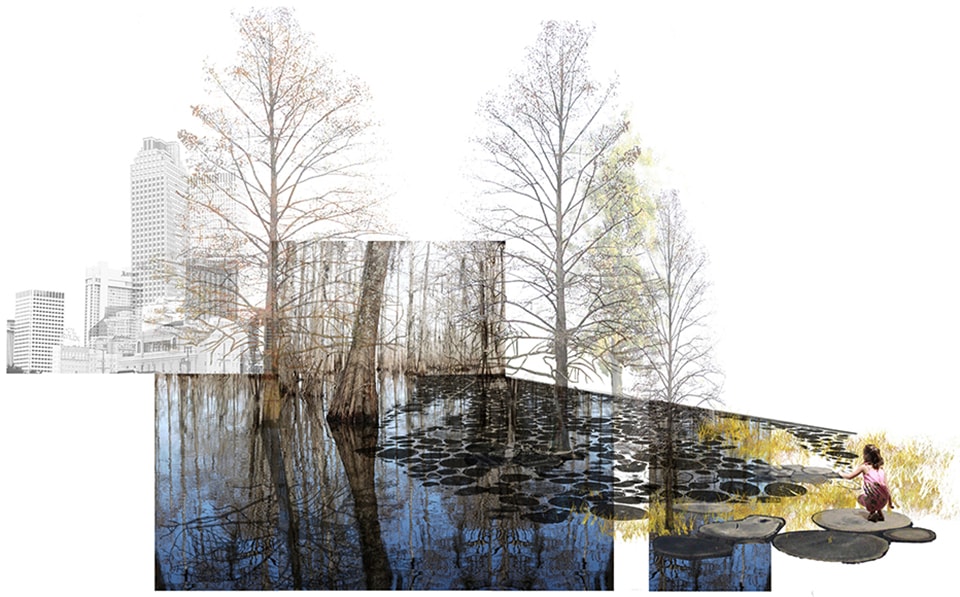

Native tree systems: Live oaks structure gathering places within the corridor as well as grand allees that expand up and out of the corridor. Pecan orchards extend out into the neighborhoods, connecting to existing schools and new ‘volun-tourism’ hubs. Cypress and Tupelo lowlands are tied to the water system that extends north through the corridor.

The site, the city, the trees

The project site of Iberville and the Lafitte Corridor suffers from a number of challenging urban features including a run-down, half-empty, public housing project and a long abandoned swath of under-utilized land. Severely disconnected from the city by fences and discontinuous streets, it is an area characterized by high rates of vacancy and lacks both vitality and function. Its location, on relatively high ground and adjacent to cultural hot spots such as the French Quarter, Congo Square, Treme, and Bayou St. John, along with recent community interest and efforts involving the site, suggest that it is prime for revitalization and sustainable re-development. Historically, the neighborhood was built on the edge of New Orleans’ backswamp, and the land, which was once covered in water-loving cypress and tupelo, was systematically drained and settled. The severe effects of this urban settlement approach and the city’s dire need for new water mitigation strategies have become more clear with each passing storm, and are an essential consideration for any future urban proposal.

Big New Orleans’ Tree Tradition: Live oaks line streets and populate small parks.

While increasingly notorious for its flooding vulnerabilities, New Orleans is better known for its unique history, and rich cultural heritage, and its trees are no exception. New Orleans’ trees, from the massive live oaks in City Park and the allées lining St. Charles Boulevard, have long been a part of the city’s structural and social identity. Their very existence as big, old trees points not only to the strength and durability of their native adaptations, but also the significance they so clearly hold for the people of New Orleans. Some recent planning proposals for New Orleans such as those examined in the ‘Dutch Dialogues’ workshops focus on the use of highly engineered strategies to help manage the city’s mounting hydrologic issues. In addition to these often hard infrastructural approaches, a softer infrastructural system could also be implemented to help alleviate the city’s hydrological burden, both on a daily basis and during large storm events. For such a system, I propose we take another look at these veteran trees of the city. We can see in their expansive canopies a basis for a simple but powerful long-term planning and planting strategy for the city, and more specifically for the re-vitalization of the LaFitte/Iberville community.

Socially Significant Species: These three planting typologies, the live oak, the pecan, and the bald cypress, are environmentally adapted, socially significant, and have attributes that can be utilized to improve hydrological, social and economic function of the site.

‘Big old tree, big new easy’

With this understanding, ‘Big Old Tree, New Big Easy’ begins and ends with the trees. The plan uses well-known attributes of three native tree typologies (the high-ground live oak, the mid-ground pecan, and the water-loving cypress) to maximize the capacity of the resulting urban canopy to manage water through evapo-transpiration, to stabilize the currently sinking ground with extensive root systems, to connect neighborhoods and promote recreation with new shade and structure, to produce valued goods such as nuts and wood, and to harbor and nurture the growth of a strong community. The native planting plan, program, and phasing strategy of this urban forest ensures the success and ability of this landscape to support such hydrologic, economic, and socially rich functions by being both physically and conceptually accessible and adaptable.

Master Plan for the Laffitte Corridor and Iberville: As the corridor structures and supports a large new urban canopy, the Iberville neighborhood is updated to support a denser residential/commercial organization, including a new ‘restaurant row,’ renovated housing, a new voluntourism center and a pedestrian-friendly core. The neighborhood connects to a transformed Louis Armstrong Park in which a number of new cultural amenities such as an outdoor concert venue, sculpture garden, and marketplace find a place among the trees and a new ‘urban swamp.’

Accessibility

In order to successfully engage community, this project relies on both physical and conceptual accessibility. Physically, the project’s programmatic locations, early phased implementation, and management are all planned to draw upon and nurture the existing community and support future growth. Maintenance-heavy areas such as orchards and community gardens are located adjacent to schools and community centers. The labor of planting and pruning trees, and harvesting fruit and wood is work that is easily managed, quickly taught, and carried out with minimal skill. This allows it to be managed by a volunteer-based, multi-generational workforce without much risk, and lends itself well to larger group participation, promoting communal interaction and engagement.

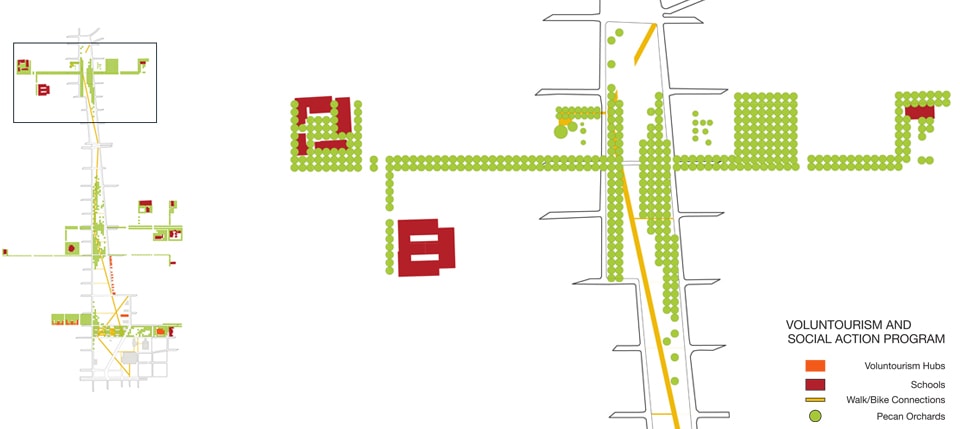

Volun-tourism and Community Connections: Pecan orchards located near schools and community centers offer both a new social program and potential industry for the corridor. The orchards become places of community interaction with both locals and ‘volun-tourists’ visiting the city.

Utilizing the availability of the city’s post-Katrina ‘volun-tourism’ work-force, provides an initial source of people and communities that already value and have experience in collective organization. The ‘volun-tourists’, people from around the country volunteering their vacation time to assisting the city in its rebuilding efforts, are able to stay in the renovated Iberville as they work with the local community and land, and in doing so, create their own connections to the neighborhood and the city. Through all this community involvement, the Lafitte Corridor becomes a place that cements cultural interaction and investment through satisfying and socially engaging work, and begins to establish what might be considered an ‘emotional value’ in the land while keeping the costs of the project lower and more attainable.

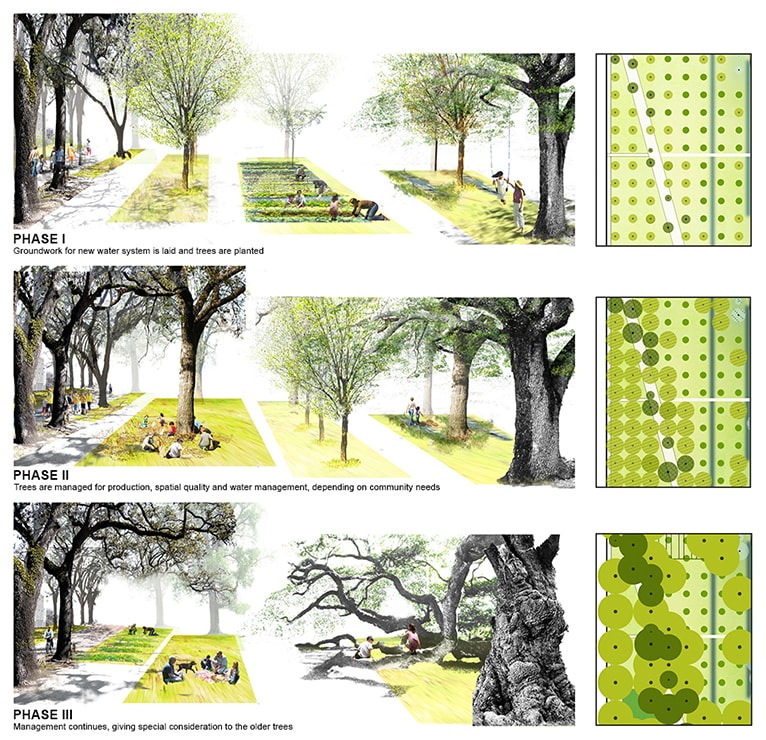

Phasing and Flexibility: The initial planting plan is meant to be flexible and adaptive to the future needs of the community. While certain trees will be managed for old growth, others are planted in tight groves that may be thinned out over time, serving as a nursery that will continually transplant the trees out into the neighborhood areas. Adaptive management will allow for the thinning out of these initial plantings to create playing fields and gardens when needed.

As they grow, the trees also begin to engage the community and realize their accessibility in new ways. Early phasing of tightly planted groves in the project require that trees be thinned out over time. This management practice not only supports the healthy maturation of old-growth trees in the corridor, but also provides a ‘nursery’ source for native trees that may be transplanted into rest of the community, allowing the maintenance of the corridor to continually populate the greater neighborhood with these trees. Such thinning efforts are particularly important to manage for the longevity of the native live oak species and promoting the accessibility of the tree’s very form. The live oak tree form holds structural qualities that in some ways speak to community more than any other old-growth tree. For unlike the towering old sequoias or the old-growth pines that survive through minimal growth to withstand extreme conditions, as the live oak grows, it extends. Its growth pattern includes shallow, long roots that often protrude upwards, and branches that reach outward and eventually downward as a result of their great density and weight. This growth pattern allows these trees to have expansive canopies that invite human interaction in the form of spaces for play or gathering.

The many possibilities for physical engagement with the trees also points to the conceptual accessibility of this project. At the most basic level there is a universal understanding in the value of trees, especially the ones we live with. Trees track the seasons with their changes and sustain us with oxygen and wood; our bodies are inextricably linked to them. Trees also reference a time scale not found in our increasingly hurried urban environment. Unfazed by human lifetimes and political cycles, trees remind us that true sustainability requires long-term investment.

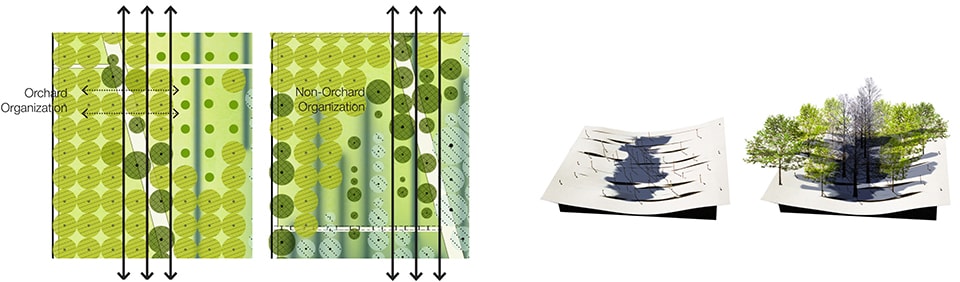

Phasing Striations and Adaptability: The striated patterning of the trees and the ground ensures visibility, structurally unifies the corridor, and promotes localized flooding and water infiltration.

Adaptability

The project’s ability to most efficiently function socially, economically, and hydrologically, lies in its overall ability to adapt thanks to flexible and responsive planting and phasing strategies. For example, through the armature of a striated planting plan, trees are planted linearly and are able to be adjusted in spacing and species in response to any number of different ground conditions. This formation creates a planting plan that provides consistency across the landscape, structurally unifying and visually connecting the entirety of the corridor. The responsive planting strategy places water-loving trees on wetter ground, pecan or harvestable trees near schools and local community organizations, and live oaks on high ground and along the main path. The simplicity of the planting plan also allows the project to continue to function under even the most lapsed maintenance. There may not be a fast and immediate return, but ‘quick fixes’ rarely hold long-term sustainable benefits As a stand of trees, the project will be able to hold a structure that is identifiable over time. Even if nothing beyond the initial planting of the trees is implemented, the trees will still provide the much needed functions of mitigating water, creating habitat, cooling urban climate, increasing the quality of our air, and ensuring another crop of ‘big, old trees’ for the next generation.

Urban Swamp: Establishment of new catchment areas and water-loving, water-absorbing trees within the corridor re-establish moments of the city’s historical swamp origins and allow for the unique experiential immersion into a true ‘urban swamp.’

This proposal received a 2011 National ASLA Honor Award in Analysis and Planning.

http://scenariojournal.com/article/big-old-tree-new-big-easy/

No comments:

Post a Comment