Published Date

Anooshey Rahim is from Houston, Texas and received her Bachelor of Arts from the University of Texas at Austin. She subsequently earned her Master of Architecture and Master of Landscape Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania. Many of her recent endeavors focus on exploring the transdisciplinary potential of a new design methodology. Her interest is to find the intersections between the entrepreneurial business sector and design thinking in order to bring new innovation to humanitarian design.

For further details log on website :

Anooshey Rahim is from Houston, Texas and received her Bachelor of Arts from the University of Texas at Austin. She subsequently earned her Master of Architecture and Master of Landscape Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania. Many of her recent endeavors focus on exploring the transdisciplinary potential of a new design methodology. Her interest is to find the intersections between the entrepreneurial business sector and design thinking in order to bring new innovation to humanitarian design.

For further details log on website :

http://scenariojournal.com/design-business/

Design Business

Welcome back! If you like what you've been reading, subscribe here to get new posts sent to you.

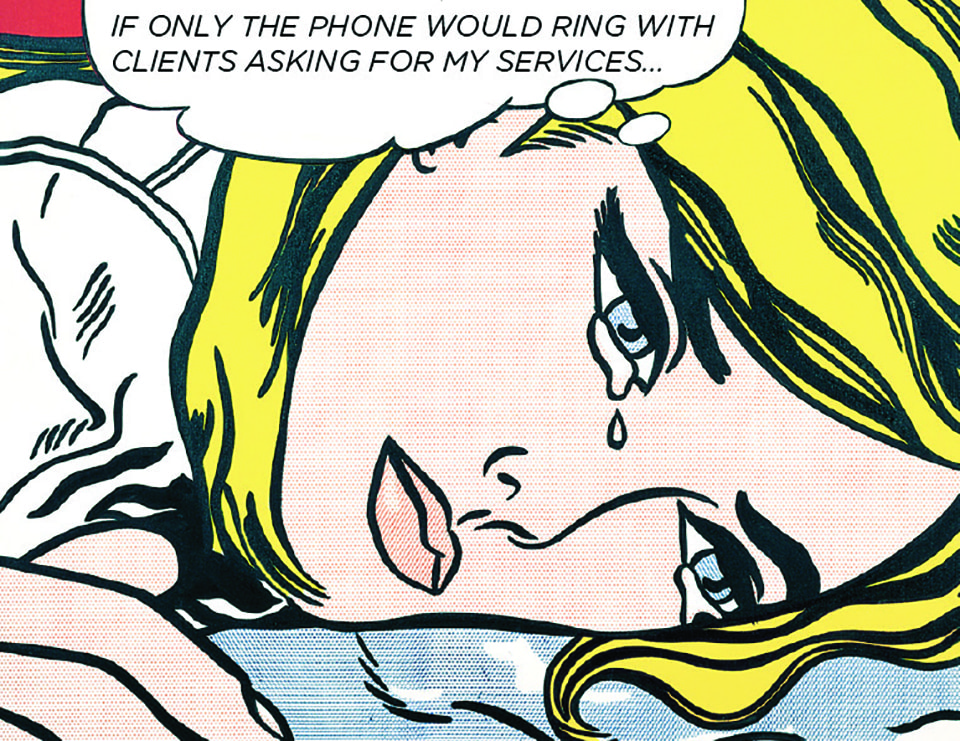

The years of the competition-driven, unpurchased idea-giving, and endless anticipation for the phone to ring deserves to be a page in history.

It often seems that for the last decade, tech firms have done a better job of advocating for design than more traditional design disciplines of architecture, landscape and graphic design. Large companies like Apple and smaller start-ups like Fitbit have distinguished themselves and succeeded by keeping design at the core of their business model. Wells Riley, a business writer and consultant, advocates for the hand-in-hand relationship of design and entrepreneurship. His sleek infographic-filled websitediscusses how design is more than a logo or website—“it’s a state of mind. It’s an approach to a problem. It’s how you’re going to kick your competitor’s ass”. If the business sector has fully embraced the power of design thinking, it should open up doors for the design field to join the conversation and learn from the creative financing and market networking of the twenty-first century start-up.

Scale/Scope, a symposium at PennDesign, brought together a diverse group of designers who are all attempting to expand the scope of their design practice. Collectively, they have come to call themselves “proactive practitioners,” often proposing projects rather than solely responding to clients. Presenters shared work on a variety of scales that collectively begin to reimagine design culture and explore this generative term. Here are some of the ideas that came out of the event.

The proactive practitioner comes in all shapes and sizes. From small, young, two-person practices to giant firms like West 8 and Gensler, many are focused on bringing social and ecological issues to the forefront of their projects. In this setting, the designers argue, social impact and ecological justice are legitimate benchmarks for design, presenting an opportunity for architects who strive to create better communities and ecological consciousness through ethical, rather than purely market-driven work. The proactive practice stems from an interest in issue-based design that may not have a direct client base to foot the bill.

Heavy Trash, an anonymous design group, built a staircase over the locked gate of a public park. This project shows how suggestive design can call attention to the problems of our built environment. Image via gray_matter(s).

Proactive projects work on many scales. Many of the projects shown at the conference were small, one-off, guerilla-style projects that land into the public realm to highlight contradiction, spur conversation, and respond to the climate. These projects typically represent a way for young designers to speak, as much as they provide meaningful change for communities or users. Many are creative, lean and strategic. Examples include the highly regarded Park-ing Day Parklet by Rebar in the Bay, and lesser known projects like the PPlanter by Hyphae Design Lab. The PPlanter is a response to the health and public facility condition, or lack thereof, in the impoverished Tenderloin area. This public toilet module, filtered and made private by large plastic planters and bamboo shoots, intendeds to be deployed on streets with no public facilities. Rebar and Hyphae Design Lab designed not just small installation projects but polemics. With Park-ing Day, Rebar took a guerrilla installation project—a modest deployment of public space utilizing a clever legal loophole—and found ways to scale it. Rebar recognized the opportunity to extend the conversation around their hijacked parking spot into a global initiative. For them, the answer was not to invest in the isolated event, but build a larger network that extended through a relational icon, the omnipresent parking spot.

Proactive design seeks to reach underserved communities who may not see themselves as clients. Moving beyond polemics and engaging directly with the people, Public Architecture‘s Day Labor Station engages an underserved population, trying to legitimize them and make them more visible. By identifying a market, with constituents and potential investors, Public Architecture engaged the population of day laborers that meet daily in parking lots to apply for work. The day laborers are an aware group with needs and priorities but no infrastructure to facilitate their much-needed occupation. The Day Labor Station synthesized programmatic needs and offered pragmatic well-designed structures for a group of unrepresented peoples who had not yet organized themselves to seek initial design assistance.

Public Architecture’s Day Labor Station identified a once-anonymous group and designed a station according to their needs. Image courtesy of Public Architecture.

Moving beyond physical designs, Emerging Terrain founder Anne Trumble has been designing public events that bring multiple groups together in cross-collaboration projects. The initial event was a public dinner party manufactured around the opening of a public art project, the Grain Elevator, in Omaha, Nebraska. With Trumble’s efforts, the party became an annual festival to celebrate the coming together of creatives in making space and food. The festival was a way for Trumble to expand the design method to include outreach and designer plus community coalitions. These events have not only brought Anne Trumble subsequent projects but became a new community amenity for the city of Omaha.

The final scale represented at the Scale/Scope symposium was that of the social network, one that extends beyond the composition of a singular space or event. MASS Design Group of Cambridge, Massachusetts, has received a lot of recognition for their Butaro Hospital project in Rwanda. The group of young designers recognized the near-absence of design in hospitals construction in the developing world, and made a case to Partners in Health’s co-founder Dr. Paul Farmer about the need for architecture to be involved in healthcare delivery. When they began, MASS had no rules for building medical facilities for developing communities. During the design of the Butaro Hospital, they worked closely with aid programs, and through this process, realized that they were designing much more than a building. MASS recognized that their hospital projects are not just health facilities but social networks that connect investors, communities, healthcare, local economies, and global public and private markets. The building of the structures become training and employment opportunities for community members that generates an internal reciprocated investment into the local economy and built fabric. In Butaro, MASS employed local craftsman and sourced local materials that led to local spin-off companies specializing in the stone building blocks used in the hospital. And by building not just for patients but doctors and their families, MASS grew the social network and provided quality facilities (including homes and schools) to encourage more physicians to settle in Rwanada. Capitalizing on the absence of sophisticated, multifaceted, social sector design work, MASS used their newfound experience with the Butaro pilot project, to develop a consultancy business that could partner with huge global organizations like USAID.

Butaro Hospital, MASS Design Group. Photo © Iwan Baan, courtesy of MASS Design Group.

Proactive practice shouldn’t have to be a sacrifice, in time nor money. By collecting and distilling successful examples of firms that have moved past the traditional client-driven model, a new rule set for instigating one’s own projects begins to emerge. Rather than relying solely on physical proposals as the main products of design, architects are experimenting with choreographing events and assembling communities, instigating conversations and networks that may in turn attract attention, investment, and further design opportunities. The social sector and true positive impact is a ripe field for designers to reorganize and build upon. By recognizing the variety of available scales in which to operate, new potential funding streams, and ways to capitalize on the entrepreneurial mindset, the twenty-first century design thinker has the world at their doorstep.

Butaro Hospital, MASS Design Group. Photo © Iwan Baan, courtesy of MASS Design Group.

The first step is to ask, how do we, as a group, adopt this new mode of practice? When in the education of the designer does this methodology become relevant? Design institutions often ignore or don’t openly acknowledge the difficulties of beginning one’s own practice and the harsh realities of realizing projects. That is not to say that school shouldn’t be about invention and speculative projections but rather also encourage innovation in the tired culture of our field.

To nimbly address current concerns, designers don’t have to stop doing buildings or other client-driven projects, but do need to expand their methodology to include proactive practice. Design firms could run lean start-ups, plug into and galvanize new markets, and be entrepreneurial and assertive enough to control their own narratives, while finding avenues to self-finance projects that they themselves have identified. The business world is the next frontier for design firms, and it is high time we look into not just designing the physical world, but also our design methodology.

http://scenariojournal.com/design-business/

No comments:

Post a Comment